在孤獨中尋找靈魂的出路:俄羅斯作曲家古拜杜林娜辭世

俄羅斯作曲家古拜杜林娜(Sofia Gubaidulina)於二○二五年三月十三日在德國阿彭(Appen)家中辭世,享壽九十三歲。她一生經歷蘇聯時代的動盪與壓力,堅持探索個人風格與精神信仰,成為二十世紀末至二十一世紀初最具代表性的作曲家之一。她的音樂以強烈的靈性深度與形式實驗著稱,橫跨宗教象徵、哲學思辨與聲響創新,深受西方現代音樂界推崇。

古拜杜林娜一九三一年出生於俄羅斯韃靼共和國的純潔城(Chistopol),父親是韃靼血統的喀山建築學院教師;母親為俄羅斯人,兩人育有三個孩子。古拜杜林娜出生幾個月後,全家遷居韃靼共和國首都喀山(Kazan),在那裡度過她的童年與青春。

古拜杜林娜的童年先後歷經史達林大清洗與二戰。在大清洗的高峰期,她親眼見到熟人一個個消失,每晚都要擔心父親被抓走。二戰期間,糧食配給不足,家中不得不變賣所有物品。喀山擠滿戰火中逃出的難民,家中也讓出一間房供難民居住,這段經歷讓她早早接觸生死與苦難,也讓她把音樂視為精神的慰藉。她曾說:「我的生活被灰色籠罩,只有跨進音樂學校的門檻時,我才感到解脫與安適。」

喀山位於伏爾加河畔,音樂傳統深厚。雖然家中沒有音樂背景,但是在鄰居的建議下,她和姐姐進入喀山第一音樂學校,向列昂季耶娃(Ekaterina Leontieva)學習鋼琴。很快地,兒童曲目無法滿足她的欲望,於是古拜杜林娜開始嘗試創作,在喀山音樂學院隨萊曼(Albert Leman)學作曲。史達林在一九五三年過世後,社會氣氛出現變化。為了尋求更廣闊的音樂視野,古拜杜林娜決定進入莫斯科音樂學院,先後師從佩伊科(Nikolai Peyko)與舍巴林(Vissarion Shebalin)。佩伊科擔任過蕭斯塔科維奇的助理,曾帶她拜訪蕭斯塔科維奇。蕭斯塔科維奇看過古拜杜林娜的作品後對她說:「祝願您走上屬於您的『錯誤』道路。」(Я вам желаю идти вашим "неправильным" путем)這句話成為日後她堅持個人風格的重要精神支柱。

一九六三年畢業後,古拜杜林娜開始創作電影配樂,其中《毛克利》(Маугли)和《稻草人》(Чучело)是最廣為人知的作品。她創作約有二十五部配樂作品,但她坦言並不喜歡這類工作,一切只是為了生計。她真正熱愛的是在莫斯科實驗電子音樂工作室(Московская экспериментальная студия электронной музыки)的創作,在這個探索前衛音樂的場所,她更能實現藝術理想。然而,這些非傳統風格的作品使她被蘇聯官方視為形式主義者,一九七九年與與同學丹尼索夫(Edison Denisov)、舒尼特克(Alfred Schnittke)等七人被列入黑名單,失去作品公開演出與出版的機會,並遭社會孤立與監視,這種情況迫使許多作曲家選擇妥協或尋求在國外發展。

古拜杜林娜以配樂維生,同時堅持創作內心真正想寫的音樂。她的平靜與堅持,來自信仰的轉變。出身穆斯林家庭的她,在一九六○年代末受俄羅斯哲學家尼古拉‧別爾佳耶夫(Nikolai Berdyaev)與鋼琴家尤金娜(Maria Yudina)影響,一九六九年受洗成為東正教徒,名字也從源自伊斯蘭文化的「薩妮亞」(Saniya)改為代表神聖智慧的「索菲亞」(Sofia)。自此,宗教成為她創作的核心動力。她的作品不以取悅觀眾為目標,而將音樂視為靈性表達,表現出一種把藝術奉獻給神的精神:「如果我的心沒有向著天國,那麼很難想像自己的身上能有藝術。」

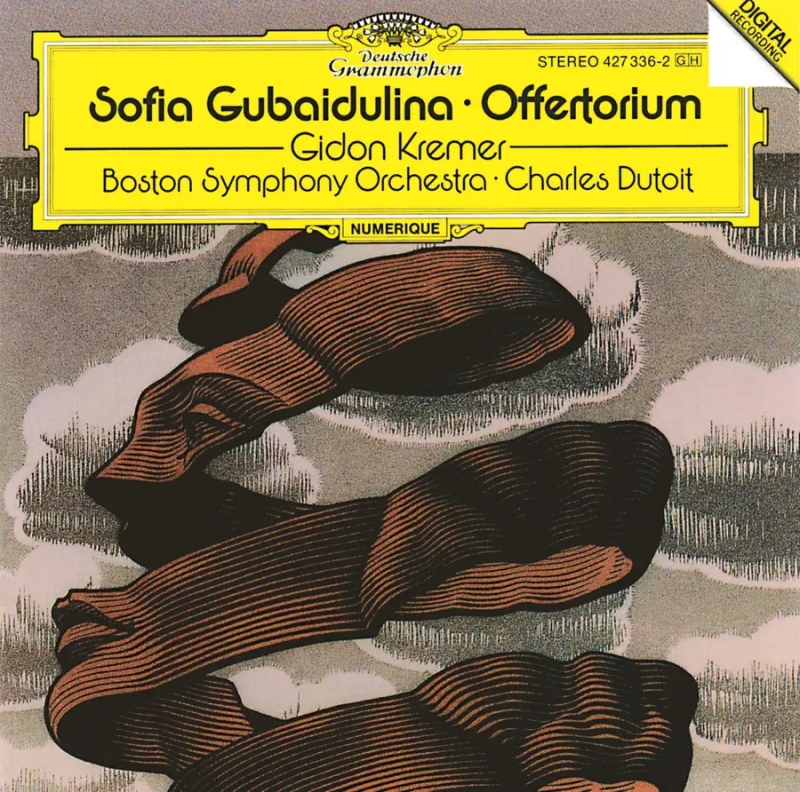

古拜杜林娜在音樂中大量運用宗教符號,例如十字架、光明與黑暗、受苦與救贖等,小提琴協奏曲《奉獻詠》(Offertorium)即為代表作。該曲取材自巴赫《音樂的奉獻》主題,以序列技法與數學比例為基礎。小提琴家克萊曼(Gidon Kremer)在西方演出後,古拜杜林娜聲名遠播。德國樂譜出版社西科爾斯基(Sikorski)也為她出版作品,建立國際聲譽。

蘇聯解體後,古拜杜林娜移民至德國阿彭隱居。阿彭位於漢堡西北方約二十公里,是一個人口不到五千人的偏遠村莊。她喜歡這裡的寧靜與自然。拒絕教學的她,刻意遠離人群只專注創作,在這裡寫下《末日之光》(The Light of the End)、為慕特(Anne-Sophie Mutter)而寫的小提琴協奏曲《當下》(In tempus praesens)、《上主之怒》(Der Zorn Gottes)、紀念同一年被列入黑名單的蘇斯林(Viktor Suslin)的《讓它如此》(So Sei Es)⋯⋯二○○一年年,她在喀山的老家被修復為「古拜杜林娜當代音樂中心」(Центр Современной Музыки С. Губайдулиной),成為展示與推廣她作品的基地。

古拜杜林娜晚年的作品愈來愈多地出現末世主題,反映她對當代世界危機的深切憂慮。對她而言,死亡不是終點,而是生命的轉化與延續。她童年面對死亡的陰影,使她更加渴望探究生命意義。她在創作中融入對永恆的信仰,將死亡視為與逝者對話的契機,並思索人類整體的命運。這樣的視角使她的音樂富含靈性與哲學深度,是一種祈禱,也是一場靈魂的追問。她不僅用音符描繪心目中的內在風景,更不斷地與時間、信仰、死亡對話。從蘇聯體制下堅持創作自由,到德國鄉間的沉潛筆耕,她的創作旅程正是一位作曲家在現代世界中尋求自我靈魂出路的寫照。在她辭世之際,我們得以重新聆聽那些曾被視為「錯誤」的聲音,看見一位作曲家如何在孤獨中稟持信仰,書寫她對這個時代的詮釋與見證。

Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina passed away on March 13, 2025, at her home in Appen, Germany, at the age of 93. She lived through the hardships of the Soviet era, remaining true to her personal musical voice and spiritual beliefs. Known for her deeply spiritual and experimental music, Gubaidulina became one of the most important composers from the late 20th to early 21st centuries. Her works are filled with religious symbolism, philosophical ideas, and bold sound innovations, earning high respect in the Western music world.

She was born in 1931 in Chistopol, in Russia's Tatar Republic. Her father was of Tatar descent and taught architecture, while her mother was Russian. They moved to Kazan, where Gubaidulina grew up, during a time of political terror and World War II. These early experiences of loss, hunger, and fear shaped her deep connection to music, which she called her only comfort in a dark world.

Though her family had no musical background, she started studying piano at a local music school. She later studied composition at the Kazan Conservatory and moved to the Moscow Conservatory to expand her musical knowledge. One turning point came when the famous composer Dmitri Shostakovich encouraged her to follow her own "wrong" path — advice that gave her strength to pursue her unique artistic voice.

After graduating in 1963, she wrote film music to support herself, with works like "Mowgli" and "Scarecrow" becoming well-known. Still, she preferred working at the Moscow Studio for Electronic Music, where she could freely explore avant-garde ideas. Her experimental style was not accepted by the Soviet authorities, and in 1979, she and several other composers were blacklisted. Her works were banned, and she lived under constant pressure.

During the late 1960s, Gubaidulina experienced a spiritual transformation. Born into a Muslim family, she was deeply influenced by Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev and pianist Maria Yudina, eventually converting to Russian Orthodoxy in 1969. She changed her name from "Saniya" to "Sofia," symbolizing divine wisdom. From then on, faith became the core of her music. She believed music was not for entertainment but a way to serve God.

Religious symbols like the cross, light and darkness, suffering and salvation appear in many of her works. Her famous violin concerto "Offertorium" is based on a theme by Bach and uses serial techniques and math patterns. When violinist Gidon Kremer performed it in the West, it brought her international fame. Her works were later published by Sikorski, a German music publisher.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Gubaidulina moved to Appen, a quiet village near Hamburg. She lived a secluded life, focused only on composing. Some of her major late works include "The Light of the End", "In tempus praesens" (for violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter), "The Wrath of God", and "So Sei Es", dedicated to her fellow blacklisted composer Viktor Suslin. In 2001, her family home in Kazan was turned into the Sofia Gubaidulina Center for Contemporary Music.

In her later years, Gubaidulina's music reflected her growing concern about the world’s crises, often exploring apocalyptic and eternal themes. For her, death was not the end but a transformation — a gateway to something beyond. She used music as a way to meditate on life, time, death, and faith. Her artistic journey, from Soviet oppression to quiet reflection in rural Germany, shows a composer in search of spiritual truth and artistic freedom.

Now, as we revisit her once "wrong" sounds, we see how Gubaidulina turned solitude into strength and gave the world a unique voice — one of deep faith, resilience, and visionary beauty.

*This English version is a concise summary of the original Chinese article.*

GUBAIDULINA Offertorium - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra; Hommage à T.S. Eliot

Gidon Kremer (violin), Boston Symphony Orchestra, Charles Dutoit

April 1988, Symphony Hall, Boston

Eduard Brunner (clarinet), Christine Whittlesey (soprano), Gidon Kremer (violin), Radovan Vlatkovic (horn), Alois Posch (double bass), Klaus Thunemann (bassoon), David Geringas (cello), Tabea Zimmermann (viola), Isabelle van Keulen (violin)

April 1987, Bibliothekssaal, Polling

發表留言