謝德林《卡門組曲》把歌聲轉換為舞影:一部愛與藝術的共生傳奇

一九六○年代的蘇聯芭蕾以《天鵝湖》、《吉賽兒》等古典作品為核心,舞台上盡是仙女與公主。莫斯科大劇院首席舞者普利謝茨卡雅(Maya Plisetskaya)早就厭倦這些溫順角色。「我不想再當仙女或公主,我要一個真實、複雜的女人。」於是,「卡門」這個追求愛情與自由,敢於挑戰權威的女性,成為她突破傳統的理想角色。

普利謝茨卡雅親自坐下來撰寫劇本,把梅里美(Prosper Mérimée)小說與比才歌劇的故事濃縮成一幕芭蕾,舞台設定在象徵命運角力的鬥牛場。她渴望創作出一部突破蘇聯保守芭蕾框架的作品。

當時蕭斯塔科維奇在蘇聯被視為最具戲劇張力與深度的作曲家,所以普利謝茨卡雅與丈夫、作曲家謝德林(Rodion Shchedrin)帶著完成劇本親自登門拜訪。除了普利謝茨卡雅認為蕭斯塔科維奇能為卡門這樣的角色創造出既具有力量又富於戲劇性的音樂,而且考慮如果由蕭斯塔科維奇創作音樂,不僅能得到權威的藝術背書,也能讓蘇聯文化體制更容易接受。只是蕭斯塔科維奇雖然對計畫很感興趣,最終還是婉拒,理由是「觀眾聽不到〈鬥牛士之歌〉、〈哈巴奈拉〉這些耳熟能詳的旋律,肯定會感到失望」,而且「我無法與比才相比」。換句話說,蕭斯塔科維奇覺得要重新創作一部卡門是行不通的。

普利謝茨卡雅把目標轉向鄰居哈察都量(Aram Khachaturian),但是哈察都量反問普利謝茨卡雅「為什麼不讓妳自己家裡的作曲家試試?」這句話讓普利謝茨卡雅意識到,懂她的舞蹈的謝德林,可能才是最適合的作曲家。

不過,謝德林同樣猶豫不定。除了對比才的敬畏,當時他的手中還有許多作品,包括歌劇《不僅是愛》(Не только любовь)待完,擔心時間與精力不足以應對《卡門組曲》的挑戰。再者,謝德林深知蘇聯文化部對現代作品的審查非常嚴格,特別是像《卡門組曲》這樣具有「性感」與現代元素的芭蕾。不過,「雖然怕文化部批評太前衛,但是我更怕讓瑪雅失望。」最後他決定和妻子一起冒險,一起承擔作品可能被禁演的後果。

莫斯科大劇院為普利謝茨卡雅保留一九六七年四月二十日的首演檔期,但是為了獲得演出許可,她必須在年初向文化部提交劇本與音樂。算一算,謝德林只有二十天的工作時間!當時普利謝茨卡雅已經年近四十歲,急需一部新作品來延長職業生涯,她天天緊盯謝德林的進度,在他身邊不停哼唱〈哈巴奈拉〉。謝德林深知《卡門組曲》對愛妻的重要性,只是笑著回答「再給我幾天。妳唱得比我寫得還快,我得趕上!」謝德林靠著無數杯濃咖啡通宵工作,而普利謝茨卡雅雖然著急,但是她擔心丈夫的心臟受不了,悄悄把咖啡換成白開水。

有了劇本與音樂,接下來就是舞蹈,但是當時沒有蘇聯編舞家願意冒險去碰一個「放蕩的吉普賽女郎」。一九六六年下半年,編舞家阿隆索(Alberto Alonso)帶著古巴國家芭蕾舞團(Ballet Nacional de Cuba)到莫斯科巡演,並受邀到莫斯科大劇院交流。他為劇院舞者示範一段佛朗明哥,動作大膽且充滿力量,融合了熱情、動感與戲劇性,與普利謝茨卡雅對卡門角色的想像相符:「看著他的動作,我心想:這就是我的卡門!他懂卡門的心跳。」再加上阿隆索是古巴籍,是蘇聯盟友,卻又不受蘇聯內部意識形態框架限制,這次會面讓她確信阿隆索是理想人選。離開莫斯科前,阿隆索告訴普利謝茨卡雅:「給我音樂,我就讓卡門動起來。」

後來,阿隆索帶著只有一個月的短期簽證與高燒來到莫斯科,謝德林的音樂還沒有完全完成,也就是說,編舞與音樂創作是同步,甚至交錯進行,形成高度緊張的創作環境。但是雙方也因此能彼此激發靈感,並及時做必要的修改。例如謝德林根據阿隆索的動作微調「命運主題」,加入更強烈的打擊樂,增強芭蕾的衝突感;阿隆索則根據音樂強化編舞的戲劇性。

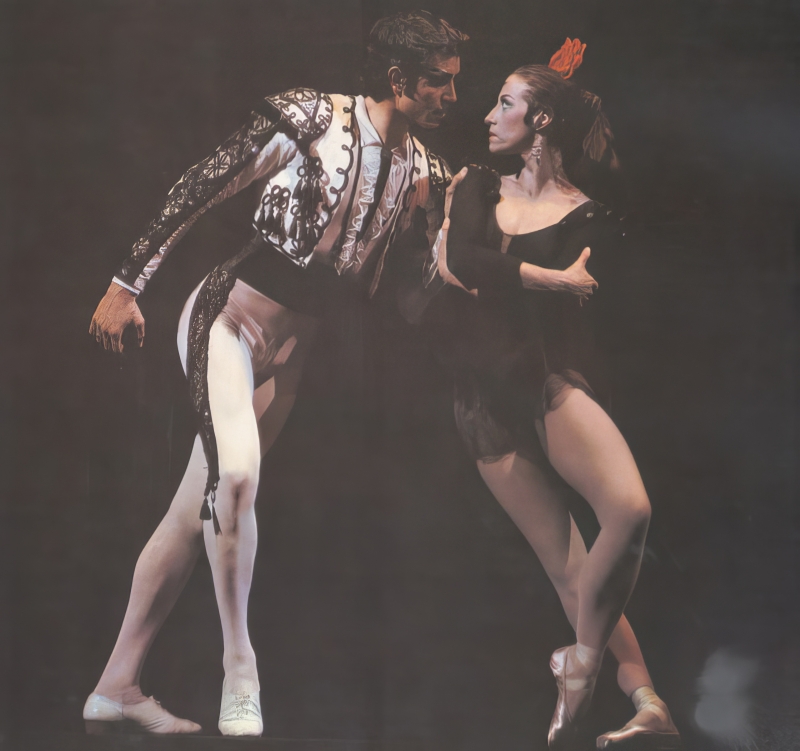

阿隆索很快完成融合古典芭蕾與佛朗明哥元素的編舞,舞台為簡約的圓形鬥牛場,普利謝茨卡雅穿紅著黑色緊身衣,以髖部擺動與手臂弧線強調卡門的叛逆。從排練初期,勉強同意演出的文化部就多次派人監督,要求提交詳細的劇本與音樂樣本。文化部長福爾采娃(Ekaterina Furtseva)親自觀看排練後,對普利謝茨卡雅的動作大為震驚,批評其「低俗」和「不芭蕾化」,要求給卡門「穿上長裙遮住大腿」,普利謝茨卡雅反駁:「卡門不是蘇聯模範工人,她是自由的女人。」

雖然首演的觀眾反應熱烈,但是福爾采娃氣到當場服用鎮靜劑,當晚即以「觀眾反應不正常」為由,取消第二場演出並且禁演。在哈察都量等藝術家公開支持下,《卡門組曲》才沒有徹底消失。後來,當高齡八十八歲的阿隆索回到莫斯科親自幫助大劇院復原作品的時候,他幽默形容當年首演結束,「福爾采娃看我的眼神就像看到(叛徒)托洛茨基(Lev Trotsky)」。

《卡門組曲》的禁令在一九七○年代解除,它不但重返大劇院的舞台,還走出蘇聯成為普利謝茨卡雅的招牌,累計演出超過三百場,延長二十年的舞台生命。即使後來移居德國,普利謝茨卡雅也以比賽、排練與復演的方式推廣這部作品。在謝德林七十歲生日那一年,七十七歲的普利謝茨卡雅再度為丈夫舞起卡門,讓謝德林落淚感嘆:「這是我寫過最好的音樂。」另一方面,從莫斯科回到古巴後,阿隆索讓古巴國家芭蕾舞團的艾莉西雅·阿隆索(Alicia Alonso),也是他的嫂子演出女主角,恢復莫斯科首演版中被刪減的激情雙人舞,並且也帶它走向國際舞台。

在音樂層面上,《卡門組曲》並非單純的音樂改編,而是一次「解構與重塑」。謝德林保留比才的旋律核心,但是徹底改變配器。創作靈感則是來自觀察普利謝茨卡雅的舞姿,特別是她的髖部動作與手臂弧線。有一次普利謝茨卡雅走進書房,發現謝德林邊寫邊模仿她的動作,試圖捕捉卡門音樂的節奏和肢體動作的契合。比才的歌劇原本使用十九世紀典型的歌劇樂隊配置,而謝德林將之壓縮成弦樂群,並擴張打擊樂,組成龐大的節奏網絡。這樣的處理不僅突出舞蹈的節奏感,也讓音樂帶有一種冷冽、現代的色彩。弦樂常以齊奏或強烈的切分節奏,營造推進的張力;打擊樂則涵蓋木魚、響板、鐵片琴、鈴鼓與定音鼓等多樣音色,賦予音樂近乎「戲劇打擊樂」的效果。謝德林解釋:「比才的旋律已經自有火焰,我只是給它加上新的火花。」

例如在〈哈巴奈拉〉中,他放慢旋律速度使音樂更具誘惑力;在〈鬥牛士之歌〉中,他透過打擊樂的重複節奏,營造鬥牛場的儀式感;在〈間奏曲〉裡,他以透明的弦樂質感營造短暫的抒情空間,成為芭蕾中少數的喘息時刻;在〈阿拉貢舞曲〉中,他則放大西班牙風格的節奏能量,與舞蹈的爆發力互為表裡。至於「命運主題」,則透過不協和音與厚重弦樂,凸顯悲劇宿命。

半世紀以來,這部作品早已超越蘇聯體制,成為全球共享的芭蕾與音樂語言。《卡門組曲》既是比才旋律的「再聲化」,也是謝德林語言的實驗場。他讓歌劇的旋律走向,透過弦樂與打擊樂的極端對比,從歌曲轉為舞蹈傾向,獲得全新的劇場生命力。從當年被禁演的「異端」到今日的「國寶」,《卡門組曲》的歷程象徵藝術家對極權的抵抗,也見證愛情與藝術的合流。對普利謝茨卡雅而言,卡門是一種生命狀態;對謝德林而言,這是他獻給妻子的最動人樂章。

In the 1960s, Soviet ballet was centered on classical works such as Swan Lake or Giselle. The stage was filled with fairies and princesses. Maya Plisetskaya, the prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theatre, had long grown weary of these submissive roles.“I don’t want to be a fairy or a princess anymore. I want to be a real, complex woman.” («Я не хочу больше быть феей или принцессой. Я хочу быть настоящей, сложной женщиной.»)

Thus, Carmen—the woman who sought love and freedom and dared to challenge authority—became her ideal role for breaking through tradition.

Plisetskaya herself sat down to write the libretto, condensing Prosper Mérimée’s novella and Bizet’s opera into a one-act ballet, with the stage set in a bullring symbolizing the struggle of fate. She longed to create a work that would break free from the conservative framework of Soviet ballet.

At the time, Dmitri Shostakovich was considered the composer with the greatest dramatic depth in the Soviet Union. Plisetskaya and her husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin, personally brought the completed script to him. Not only did Plisetskaya believe Shostakovich could provide music of great power and drama for Carmen, but she also hoped that if the music came from him, the ballet would carry authoritative artistic legitimacy and more easily win acceptance from the Soviet cultural establishment. Shostakovich, though intrigued by the idea, declined, saying:

“If the audience doesn’t hear the familiar tunes—the Toreador Song, the Habanera—they will surely be disappointed. And besides, I cannot compete with Bizet.” («Если публика не услышит знакомых мелодий — “Арии Тореро”, “Хабанеры”, — она наверняка будет разочарована. А кроме того, я не могу соревноваться с Бизе.»)

In other words, he felt composing a completely new Carmen was impossible.

Plisetskaya next turned to her neighbor Aram Khachaturian, who instead asked her: “Why not let the composer in your own household try?” («Почему бы не дать попробовать вашему домашнему композитору?»)

This made her realize that Shchedrin—who understood her dancing better than anyone—might actually be the best choice.

But Shchedrin, too, hesitated. Out of respect for Bizet, and because he already had unfinished works on hand, including the opera Not Only Love, he worried about lacking the time and energy for such a challenge. He was also acutely aware of the strict censorship by the Ministry of Culture, especially toward modern works like Carmen Suite, with its “sensual” and modern qualities. He later recalled: “I was afraid the Ministry would criticize it as too avant-garde, but I was even more afraid of disappointing Maya.”

( «Хотя я боялся, что Министерство культуры сочтёт это слишком авангардным, я ещё больше боялся разочаровать Майю.»)

In the end, he decided to take the risk with his wife, knowing they might face the ban of the entire project together.

The Bolshoi Theatre had already reserved the premiere slot for April 20, 1967. But to obtain approval, the libretto and score had to be submitted to the Ministry at the beginning of the year. That meant Shchedrin had only twenty days to compose the music! Plisetskaya, already nearly forty, desperately needed a new role to extend her career. She hovered around him, singing the Habanera to keep him moving. Shchedrin, knowing how much the work meant to her, joked:

“Give me a few more days. You’re singing faster than I can write—I have to catch up!” («Дай мне ещё несколько дней. Ты поёшь быстрее, чем я пишу — мне нужно догонять!»)

Fueled by countless cups of strong coffee, he worked through the nights, while Plisetskaya, worried about his heart, quietly replaced the coffee with plain water.

With libretto and music ready, the next challenge was choreography. But no Soviet choreographer was willing to take on a “promiscuous gypsy woman.” In late 1966, Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso came to Moscow with the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Invited to the Bolshoi, he demonstrated flamenco steps that were bold and powerful, full of passion and drama—exactly how Plisetskaya imagined Carmen. “Watching his movement, I thought: this is my Carmen! He knows the heartbeat of Carmen.” («Смотря на его движения, я подумала: вот она, моя Кармен! Он знает её биение сердца.»)

Since Alonso was Cuban—an ally of the Soviet Union, yet not bound by its ideological restrictions—he was the perfect candidate. Before leaving, he told Plisetskaya: “Give me the music, and I’ll make Carmen move.” («Дайте мне музыку, и я заставлю Кармен двигаться.»)

Alonso returned to Moscow on a short visa, burning with fever, even as Shchedrin was still finishing the score. Music and choreography progressed simultaneously, sometimes even crisscrossing. The pressure was immense, but it also created a space for mutual inspiration. For example, Shchedrin adjusted the “Fate Theme” with more percussion to heighten dramatic tension, while Alonso amplified the theatricality of the dance to match the music.

He quickly devised choreography blending classical ballet with flamenco, set on a bare circular bullring stage. Plisetskaya, in a black-and-red leotard, emphasized Carmen’s rebelliousness through hip movements and sweeping arm gestures. From the start, the Ministry of Culture kept a close watch, demanding detailed scripts and score samples. Minister Ekaterina Furtseva personally attended rehearsals and was shocked. She called the work “vulgar” and “un-ballet-like”, and insisted Carmen should wear a long skirt to cover her thighs. Plisetskaya retorted: “Carmen is not a Soviet model worker. She is a free woman.” ( «Кармен — не советская передовичка. Она — свободная женщина.»)

The premiere provoked a storm. The audience responded with enthusiasm, but Furtseva, furious, reportedly took tranquilizers on the spot and that very night banned further performances, citing “abnormal audience reactions.” Thanks to the public support of figures like Khachaturian, Carmen Suite did not disappear entirely. Years later, when Alonso returned to Moscow at age eighty-eight to help reconstruct the ballet, he joked: “After the premiere, Furtseva looked at me the way one would look at Trotsky.” ( «После премьеры Фурцева смотрела на меня так, как смотрели бы на Троцкого.»)

The ban was lifted in the 1970s. Carmen Suite not only returned to the Bolshoi but also traveled abroad, becoming Plisetskaya’s signature role. She danced it more than 300 times, extending her career by two decades. Even after moving to Germany, she promoted the ballet through competitions, rehearsals, and revivals. At Shchedrin’s 70th birthday concert, the 77-year-old Plisetskaya once again danced Carmen, moving her husband to tears:

“This is the best music I have ever written.” («Это лучшая музыка, которую я когда-либо написал.»)

Meanwhile, Alonso staged the work in Cuba with Alicia Alonso (his sister-in-law) as Carmen, restoring the passionate duet cut in Moscow, and brought it to international stages.

Musically, Carmen Suite was not a simple arrangement but an act of “deconstruction and reconstruction.” Shchedrin preserved Bizet’s melodic core but completely reimagined the orchestration. His inspiration came from watching Plisetskaya’s movements, especially her hips and arms. Once, she entered his study and found him imitating her gestures as he wrote, trying to capture the rhythm of her body in sound. Whereas Bizet had employed a standard 19th-century opera orchestra, Shchedrin compressed it into strings and expanded the percussion into a vast rhythmic web. This not only heightened the dance’s pulse but also gave the music a sharp, modern edge. Strings often played in unison with strong syncopations, while percussion included woodblocks, castanets, glockenspiel, tambourine, and timpani, creating an effect close to “percussion theatre.” Shchedrin explained:

“Bizet’s melodies already contain fire. I merely added new sparks.” («Мелодии Бизе уже несут в себе огонь. Я лишь добавил к ним новые искры.»)

For example, in the Habanera, he slowed the tempo to make it more seductive; in the Toreador Song, he used pounding percussion to evoke the ritual of the bullring; in the Intermezzo, transparent strings offered a rare lyrical interlude; in the Aragonaise, he magnified the Spanish rhythms to match the dance’s explosive energy. As for the “Fate Theme”, dissonance and heavy strings underlined the sense of tragic destiny.

Over half a century, the work has transcended Soviet cultural politics to become a shared language of ballet and music worldwide. Carmen Suite is at once a “re-sonification” of Bizet’s melodies and an experimental laboratory for Shchedrin’s own voice. By transforming operatic tunes through the stark contrasts of strings and percussion, he shifted them from song into dance, giving them new theatrical vitality. From its initial ban as heresy to its status today as a classic, Carmen Suite symbolizes artists’ resistance to authoritarianism and testifies to the union of love and art. For Plisetskaya, Carmen was a state of being; for Shchedrin, it was the most moving music he ever gave to his wife.

發表留言