「歷史詮釋演奏」帶動全新演奏哲學:長野健的布拉姆斯《德意志安魂曲》再思考

二○一一年夏季,當時擔任蒙特利爾交響樂團(Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal)音樂總監、巴伐利亞國家歌劇院總音樂總監的指揮家長野健(Kent Nagano)與科隆古樂團(Concerto Köln)首度合作。由於錄音選曲以及過去安排樂季節目時的曲目偏好,長野健一直被歸類為支持現代音樂的指揮家。事實上,他對「歷史詮釋演奏」(Historically Informed Performance, 簡稱HIP)也頗感興趣。這一次與科隆古樂團的合作,讓曾經嘗試使用歷史樂器,或是研究歷史表演風格的長野健像是靈光被點燃般,積極投入接觸與研究這個領域。

何謂HIP?從「歷史考據」走向「知識詮釋」

文章正式開始之前,我想先談談「歷史詮釋演奏」這個名詞。一般人看到它,可能會先想到標榜忠實使用作曲家創作當下發展中的樂器與演奏方法,例如不能使用漸強漸弱的「古樂運動」。然而,十八、十九世紀的聲音未曾留下錄音記錄,因此所謂「重現原貌」本身就是一種主觀的推想,往往存在不同方向的理解與詮釋。再加上喜歡冒險創新的演奏家,也不甘於創意被樂器的表現力束縛,於是即使同樣標榜「仿古演出」,也很快發展出許多種互有差異的演出樣式。

我想借用「古樂運動」前輩阿農庫爾(Nikolaus Harnoncourt)的話來說明:所謂的「真實性」不是單純模仿舊風格,而是了解音樂的內在邏輯和美學本質,進而放到自己的詮釋邏輯裡。阿農庫爾之所以演出巴赫與蒙台威爾第的作品,並非因為這些作品屬於某個歷史時代,而是因為它們的音樂理念與表達方式可以超越時空,在當代仍具有表達力;阿農庫爾的演出曲目、使用的樂器考量點不在複製時代,而是能不能實現自己認知的音樂理念。因此,我認為HIP譯成「歷史詮釋演奏」會比慣用的「歷史考據演奏」更恰當,因為Informed這個字還有「經過研究與理解、受知識引導啟發」的意思。所以持「歷史詮釋演奏」的演奏家,既不拘泥於復古,也不是天馬行空的恣意妄為。關鍵在對音樂本質是否做過深入研究理解,至於要選擇使用哪一種樂器,那就看演奏者受到什麼樣的啟發而定,是次要的議題。

演出即研究:長野健的詮釋實驗與跨界合作

二○一六年夏天再度和科隆古樂團合作莫札特《伊多曼尼奧》(Idomeneo)之後,長野健和科隆古樂團於二○一七年九月在科隆大學舉辦 「華格納詮釋」(Wagner Lesarten)研討會,結合音樂學、歷史學與表演藝術來重新分析華格納的總譜與十九世紀不同國家的表演習慣與偏好。二○二○年,長野健指揮科隆古樂團與德勒斯登音樂節管弦樂團(Dresdner Festspielorchester)聯合樂團,以音樂會型式演出《萊茵黃金》來呈現研究成果,並在接下來的樂季陸續安排上演《尼貝龍的指環》其他三部。除了科隆古樂團,長野健同一時間也採用HIP的角度演出莫札特、貝多芬的作品,或是和歐洲古樂團合作演出巴赫。

那麼,長野健的「歷史詮釋演奏」核心觀點是什麼呢?

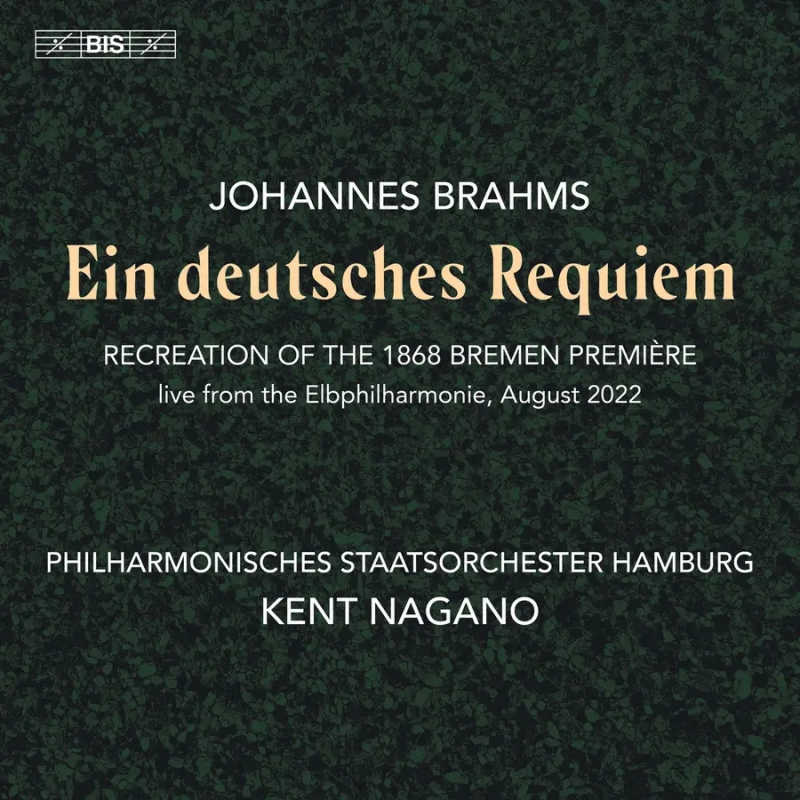

首先當然是「接近作曲家的原意」。長野健認為,透過深入研究歷史文獻、原始樂譜以及當時的表演習慣,演奏者才能真正理解作曲家的創作動機與音響想像。目的不是為了重現「過去的正確」,而是建立理解與詮釋的基礎,讓演奏更具說服力與歷史感。畢竟古往今來樂器性能和演出環境有許多異動,但作曲家心中的「理想」只有一種。所以你要忠實追求創作者的「心」?還是照搬某個特定時空下的「型」呢?長野健非常強調學術研究與演出實踐的結合,他相信,詮釋應該建立在清楚的研究基礎上,而非純粹的直覺或習慣。同時,長野健也肯定當代表演者與觀眾的詮釋自由,認為作品完成後便進入公共領域,應該允許聽眾自己去理解,這是一種活的詮釋哲學。因此他強調歷史詮釋演奏不等同於歷史的複製,它注重的不只是古樂圈講究的技術手法,更是在理解作品文化與社會背景的基礎上,開展出來的詮釋空間。這種詮釋觀點,可以在長野健二○二五年與漢堡愛樂出版的布拉姆斯《德意志安魂曲》(Ein deutsches Requiem)一窺端倪。

布拉姆斯《德意志安魂曲》:歷史背景與選曲邏輯

二○二二年八月,長野健與漢堡愛樂、總計近四百名歌手的九個合唱團,在漢堡易北愛樂廳(Elbphilharmonie)演出布拉姆斯《德意志安魂曲》。仔細看唱片的曲目,會發現它只有六個樂章,而且樂章中間穿插改編成小提琴與管風琴編制的巴赫第一號小提琴協奏曲第二樂章、塔替尼降B大調小提琴協奏曲第二樂章、舒曼《晚間歌曲》(Abendlied,op. 85-12)。最後以巴赫《馬太受難曲》〈主啊,請賜垂憐〉(Erbarme dich mein Gott),以及三首莫札特改編的德語版韓德爾《彌賽亞》〈看哪,神的羔羊〉(Kommt her und seht das Lamm)、〈我知道我的救贖主活著〉(Ich weiß, dass mein Erlöser lebet) 與〈哈利路亞〉(Halleluja)結束,《德意志安魂曲》女高音獨唱的第五樂章〈如今,你們固然感到憂愁〉(Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit)則不見了。這是怎麼一回事?

《德意志安魂曲》是布拉姆斯一八六○年代的作品,當時的布拉姆斯不只是一名在喪母悲痛中尋求精神昇華的作曲家,也是在人際關係與信仰邊界中尋找語言與音樂出口的思想家,更是藝術上正從青年時期的狂飆邁入壯年成熟期的音樂家。一八六七年十二月在維也納試演兩個樂章後,布拉姆斯修改當中的節奏與聲部平衡問題,一八六八年四月十日在布來梅主教座堂(Bremer Dom)親自指揮首演。 一八六九年二月十八日,布拉姆斯在維也納愛樂之友協會音樂廳(Musikvereinsaal)再度親自指揮《德意志安魂曲》,這次加入第五樂章〈如今,你們固然感到憂愁〉,也就是現今熟悉的版本。而長野健與漢堡愛樂演出的,是在布來梅主教座堂首演版本的原貌。

一八六八年四月十日是「聖週五」(Good Friday),也就是復活節前的星期五。在基督宗教裡,紀念耶穌基督受難與死亡的聖週五是非常重要的節日,音樂自然要強調耶穌基督的受難與復活。只是《德意志安魂曲》的歌詞選自路德教派聖經,強調「以母語直接向神祈禱」的思想;選擇歌詞時,布拉姆斯又把焦點放在哀悼與安慰,死亡與復活等普世主題,刻意使用間接的文本來提及基督的受難與復活,與主教座堂的期待不符。於是,布拉姆斯以巴赫、韓德爾的作品來補充宗教內容。當時聖週五「神聖音樂會」(Geistliches Concert am Charfreitag)也兼具市民音樂會的性質,為了緩解音樂情緒讓聽眾有喘息的空間,布拉姆斯選擇巴赫、塔替尼的小提琴作品當成過場。舒曼的作品則是出布拉姆斯個人紀念恩師逝世五週年的心意,由擔任小提琴獨奏的姚阿幸(Joseph Joachim)改編。當天在巴赫、韓德爾作品擔任獨唱的,是約阿幸夫人阿梅琳‧姚阿幸(Amalie Joachim)。最後氣氛突兀的〈哈利路亞〉合唱是十九世紀德國音樂節最常選用的終曲,用來表現市民音樂會的歡慶氣氛。

不是複製歷史,而是重建脈絡:長野健的演出理念

長野健的HIP不只是單純刪去第五樂章、回復穿插作品等表面功夫,而是把這一場演出視為「活的體驗」,目的在讓聽眾感受布拉姆斯意圖。首先是和德國呂別克布拉姆斯研究所(Brahms-Institut)當時的總監桑德伯格博士(Dr. Wolfgang Sandberger)合作,除了確認一八六八年首演版本的樂譜與結構,也考證推估當時合唱團與樂團的規模。除此之外,他們也研究布拉姆斯喜歡的某些舊式對位音樂風格,例如聲音清晰通透避免沉重感、中間聲部要聽得清楚、節奏變化要靈活自然,並把這些特色當作演出時的重要參考。桑德伯格博士還幫助長野健理解聖週五「神聖音樂會」對當時社會的意義,以及宗教界對作品有意見的理由。

根據桑德伯格博士的考據,當時樂團編制的弦樂人數比現行更多,長野健因此調整樂團的弦樂配置;阿梅琳‧姚阿幸的音域橫跨高音女高音與低音女中音,所以他選擇音域相仿的美國女中音凱特·林賽(Kate Lindsey)。從史料上看,一八六八年使用由教會與社區合唱團組成的一百多人合唱團,長野健的合唱團員符合非專業性質,為什麼人數卻高達四百人?

空間、音響與規模:再現布來梅的感官經驗

根據記載,當時合唱團在布來梅主教座堂以「數百人的龐大聲響」,營造出「節慶式」的震撼效果。約二一○○座位的易北愛樂廳比布來梅主教座堂更大,而且混響時間約二點二秒,主教座堂可能長達四到六秒。在實現歷史意圖而非機械複製的前提下,長野健決定擴大合唱團規模以確保聲音能填滿空間,並且傳達類似布來梅主教座堂的音量與情感飽滿度。易北愛樂廳的觀眾席採用以舞台為中心,觀眾席呈階梯狀環繞,分為多個獨立「梯田」區塊的葡萄園式設計,四百人合唱團位在中間層圍繞舞台的觀眾席,團員間的物理距離較遠,聲音平衡成為演出與錄音時的技術挑戰。但是長野健形容,長期演奏歌劇的漢堡愛樂有「音樂雷達系統」,能在複雜聲場中精準定位與平衡遠距離聲部,確保音樂的和諧與透明度。

長野健曾引用他深受影響的作曲家梅湘(Olivier Messiaen)的觀點,主張「速度標記」只是情緒提示,而非絕對標準;速度應根據演出場地的聲學環境與聽眾的聆賞經驗調整。梅湘完全不在樂譜上寫明節拍器標記,現有的標記都是妻子伊馮娜‧洛里奧(Yvonne Loriod)在後期添加,而且僅供參考。布拉姆斯同樣移除節拍器標記,而且速度標記和梅湘類似,都是提供詮釋者一種音樂的空間感、敘事節奏、甚至是情緒或靈性上的狀態,而非機械式的客觀數值。於是在第二樂章〈凡有血肉的都似草〉(Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras),我們聽到溫和的行進式節奏,強調合唱的柔和動態與對位線條清晰度。

從布拉姆斯到現代:速度、動態與HIP的未來觀點

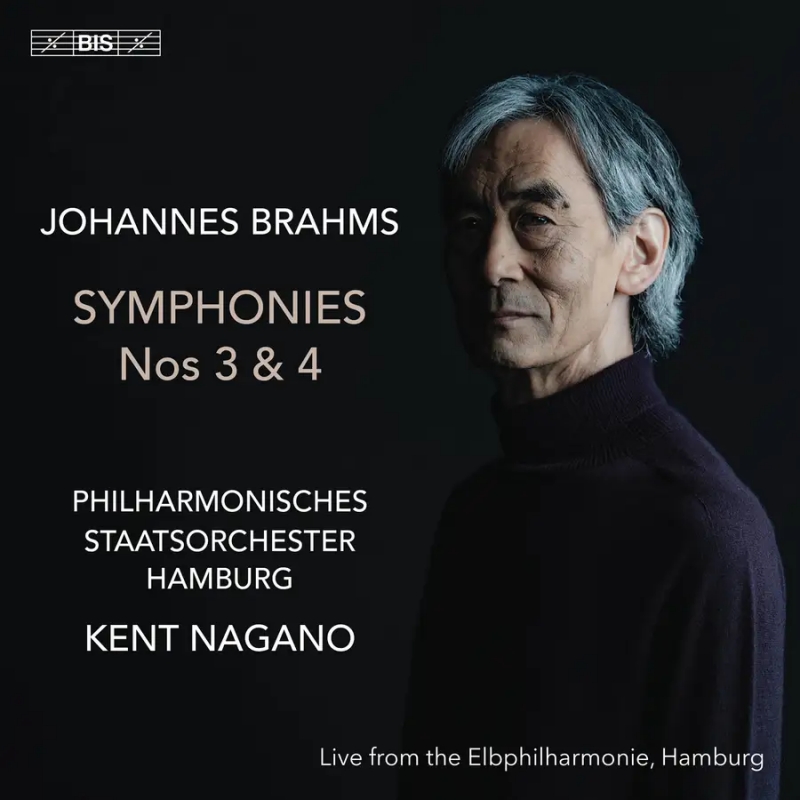

緊接著《德意志安魂曲》之後出版的第三、四號交響曲,同樣也能聽到強調內聲部和動態靈活性的HIP觀點,特別是長野健個人深有共鳴的第四號交響曲。值得一提的是,長野健特別引用荀貝格一九四七年的文章《布拉姆斯:一位進步派作曲家》(Brahms the Progressive)的觀點,認為這部「近乎激進」(nearly a radical signpost towards the future)的作品,是透過諸如古老的巴洛克舞曲「帕沙加利亞」等形式來表達新音樂的概念,展示如何結合傳統與創新,而不是保守的回顧。

荀貝格在文中就是以第四號交響曲第四樂章「帕沙加利亞」為例,闡述其「發展性變奏」(developing variation)如何預示序列音樂的結構邏輯。文章不僅為布拉姆斯正名,也反映荀貝格對音樂史的演化思考,把布拉姆斯置於從巴赫到現代主義的發展脈絡中。後來的二十世紀的作曲家,如荀貝格、貝爾格、魏本、亨德密特都在自己的作品使用類似帕沙加利亞的變奏結構。

透過「華格納詮釋」與布拉姆斯《德意志安魂曲》的歷史詮釋演出,長野健展現HIP也可以是「活的詮釋哲學」的可能性。他的做法不僅是技術層面的復原,更是一種對作曲家意圖、文化背景與當代聽眾體驗的深思熟慮的整合。這種跨學科、跨時代的音樂實踐,重新定義如何讓經典作品在現代語境中保持如新的生命力,為音樂詮釋開闢新的視角。

Summer 2011 marked the first collaboration between conductor Kent Nagano—then Music Director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal and General Music Director of the Bavarian State Opera—and the period-instrument ensemble Concerto Köln. Due to his programming and recording choices, Nagano had long been categorized as a champion of modern music. However, he also harbored a keen interest in Historically Informed Performance (HIP). This encounter with Concerto Köln seemed to ignite a spark, leading him to further explore the use of historical instruments and performance styles.

Before delving into the article, I would like to briefly reflect on the term “Historically Informed Performance." To the general audience, it often brings to mind the early music movement that strictly adhered to period instruments and rejected dynamic markings like crescendo and decrescendo. But since no audio recordings exist from the 18th and 19th centuries, recreating the “authentic sound" is inherently speculative and subject to interpretation. Moreover, adventurous performers, unwilling to be constrained by the limitations of period instruments, have developed varying styles even within the HIP label.

In this context, Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s insights are illuminating. For him, authenticity was not about mimicking old styles but understanding the music’s internal logic and aesthetics, then incorporating that understanding into one’s interpretive choices. He performed works by Bach and Monteverdi not simply because they were historically significant, but because their musical ideas and expressions remained relevant and powerful. Thus, for Harnoncourt, instrument choice was secondary to realizing a musical vision. This is why I prefer translating HIP as “Historically Informed Interpretation," rather than the more commonly used “Historically Accurate Performance," since the term “informed" implies study, insight, and inspiration. Performers engaged in HIP are neither slavishly antiquarian nor recklessly freewheeling; what matters is whether their interpretations are grounded in thoughtful research and understanding. Instrument choice then becomes a tool, not a goal.

In the summer of 2016, Nagano reunited with Concerto Köln for a performance of Mozart’s “Idomeneo". This collaboration evolved into the 2017 symposium “Wagner Readings" at the University of Cologne, where musicians, historians, and scholars came together to analyze Wagner’s scores and nineteenth-century performance practices. In 2020, Nagano led a combined ensemble of Concerto Köln and the Dresdner Festspielorchester in a concert performance of “Das Rheingold", showcasing the results of their research. Subsequent seasons featured the rest of the “Ring" cycle. Simultaneously, Nagano applied HIP principles to works by Mozart and Beethoven, and collaborated with other early music ensembles on performances of Bach.

The primary aim, according to Nagano, is to get closer to the composer’s intentions. By studying historical documents, original scores, and contemporary performance customs, performers can better understand a composer’s creative motivations and sonic ideals. This is not about restoring some fixed “correct past," but establishing a firm basis for interpretation that adds depth and historical dimension. Since instrument construction and concert environments have changed over time, it’s the composer’s artistic vision that remains constant. Nagano thus advocates for a synthesis of scholarly research and artistic practice. At the same time, he upholds the freedom of modern performers and audiences to interpret music on their own terms. He views HIP not as a rigid recreation, but as an interpretive philosophy that emphasizes cultural and historical context.

A case in point is Nagano’s 2022 performance of Brahms’s “Ein deutsches Requiem" with the Hamburg Philharmonic and nine choirs totaling nearly 400 singers, held at the Elbphilharmonie. Curiously, the performance included only six movements, omitting the well-known fifth movement soprano solo. In its place were interpolations: the second movements from Bach’s Violin Concerto No. 1 and Tartini’s Violin Concerto in B-flat (arranged for violin and organ), Schumann’s “Abendlied", Bach’s “Erbarme dich" from the “St. Matthew Passion", and three choruses from Mozart’s German-language adaptation of Handel’s “Messiah".

Why these changes? Brahms originally conducted the six-movement version on Good Friday, April 10, 1868, at Bremen Cathedral. Since this was a sacred concert, the clergy expected clearer references to Christ’s passion and resurrection. However, Brahms’s chosen texts from the Lutheran Bible were more ecumenical and universal, lacking direct mentions of Jesus. To address this concern, Brahms inserted these interpolated works by Bach and Handel. The concert also functioned as a civic music event, requiring a festive atmosphere. Pieces like Schumann’s “Abendlied" honored Brahms’s late mentor, and the “Hallelujah" chorus served as a traditional festival finale.

Nagano’s project was more than a revival of the performance order. In collaboration with Dr. Wolfgang Sandberger of the Brahms-Institut, Nagano verified the original score and studied the performance scale and acoustics of the 1868 premiere. For instance, archival notes mention the use of “hundreds and hundreds" of singers. To emulate this, Nagano assembled a large choir drawn from local community groups. Since the Elbphilharmonie is larger and acoustically different from Bremen Cathedral, he adjusted the ensemble size to match the intended sonic impact. The performance space’s vineyard-style seating created technical challenges for balance, but the Hamburg Philharmonic, with its operatic sensitivity, managed the spatial acoustics adeptly.

Nagano also referenced Olivier Messiaen’s belief that tempo markings are emotional suggestions rather than metronomic absolutes. Like Messiaen, Brahms eventually removed metronome marks from his scores, using descriptive terms instead. In the second movement “Denn alles Fleisch", Nagano chose a moderate, flowing pace that highlighted contrapuntal clarity and nuanced dynamics.

This HIP-informed approach extended to Brahms’s later symphonies, especially the Fourth, which Nagano views as almost radical. Citing Schoenberg’s 1947 essay “Brahms the Progressive", he emphasized the symphony’s use of Baroque forms like the passacaglia in the final movement, seeing it as a synthesis of tradition and innovation.

Through his work with Concerto Köln and his historically informed performances of Wagner and Brahms, Nagano exemplifies a living HIP philosophy. His approach is not about rigid historical reenactment, but a dynamic integration of research, context, and artistic vitality—revitalizing classic works for modern ears.

BRAHMS Ein Deutsches Requiem (1868 Bremen Premiere)

Kate Lindsey (mezzo-soprano), Jóhann Kristinsson (baritone), Veronika Eberle (violin), Thomas Cornelius (organ), Chor der KlangVerwaltung, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg, Kent Nagano

August 2022, Großer Saal, Elbphilharmonie

BRAHMS Symphonies Nos. 3 & 4

Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg

Kent Nagano

April 2023; January 2019, Großer Saal, Elbphilharmonie

發表留言