證據導向,尋訪初衷:「歷史詮釋演奏」宗師諾林頓辭世

英國指揮家諾林頓(Sir Roger Norrington)於二○二五年七月十八日逝世,享壽九十一歲。他以推動「歷史詮釋演奏」(Historically Informed Performance,簡稱HIP)聞名,尤其傾向「證據導向」(evidence-based music)的詮釋觀點,主張嚴格遵循作曲家的原稿指示,如節拍器標記、樂團編制,而且採用「純音風格」(Pure-Tone Style)演奏,也就是不使用揉弦(vibrato),讓音樂回歸時代原貌,避免沾染浪漫主義的浮誇。這位指揮家不僅是表演者,更是舉世聞名的音樂歷史研究者。

諾林頓一九三四年出生於英國牛津,父親是學者,母親是業餘鋼琴家,兩人在業餘製作吉爾伯特(William Gilbert)與蘇利文(Arthur Sullivan)歌劇的時候相識,因此諾林頓從小的家庭教育就是結合學術研究與音樂演出。諾林頓童年時期學習小提琴與參加合唱團,在劍橋大學主修英國文學,畢業後在牛津大學出版社工作,期間業餘從事小提琴、聲樂與指揮活動,直到一九六○年代才轉向專業道路。

他在一九五○年代晚期進入倫敦皇家音樂學校(Royal College of Music),師從指揮家包爾特(Sir Adrian Boult)學習,一九六二年為了演出十七世紀德國作曲家海因里希‧舒茲(Heinrich Schütz)的作品而成立舒茲合唱團(Schütz Choir)。回憶起這個生涯轉折點,諾林頓表示:「當時沒有人知道怎麼演奏舒茲的音樂,沒有一套可靠明確的詮釋法則,所以我得靠研究歷史資料,自己摸索出一種演奏風格。」這次穿越時光找答案的經驗,奠定了往後諾林頓歷史表演探索的基礎。

舒茲合唱團初期與倫敦巴洛克古樂團(London Baroque Players)合作演出,諾林頓在一九七八年再創立倫敦古典演奏家古樂團(London Classical Players,LCP),逐漸從巴洛克延伸至古典與浪漫時期。諾林頓形容這過程如「從十七世紀往前推演」,每次探索新時期都像發現新大陸。

諾林頓在一九六九年出任肯特歌劇院(Kent Opera)音樂總監,漸漸擴大他在英國樂界的影響力。他在這裡指揮過四十多部歌劇,演出場次達四百場。倫敦古典演奏家古樂團成立後,一九八六年到八八年錄製的貝多芬交響曲全集成為他的里程碑代表作。這一套錄音採用古樂器,遵循節拍器速度標記,避免使用揉弦,讓音色呈現古典時期純粹的透明感,音樂充滿活力與新鮮感,帶來清晰、銳利、戲劇性極強的聲響,改變人們對貝多芬慣常的想像。

所謂「證據導向」為核心的演奏理念,主張音樂演奏須依據歷史樂譜、文獻與作曲家的註記進行,而非靠演奏者的主觀解釋。他強調:「音樂不需要詮釋,只需正確呈現,音樂就會自然流露。」這一理念源自其早期研究十七世紀音樂的經驗,然後逐漸應用至十九世紀作品。例如遵守作曲家節拍器標記,貝多芬是早期使用現代節拍器標註法的人,依他所標註的快速度節奏,《英雄》交響曲聽來會充滿冒險而非莊嚴崇高。他視貝多芬為「晚期海頓」,強調他的機智與幽默,而非早期華格納式的壯闊戲劇性。曾有人批評他的《英雄》「不夠英雄」,諾林頓回應:「英雄不必一定要像是花園中被圍欄環繞的銅像。」用貝多芬註記的節拍與古樂器演奏,已經足夠忠實再現貝多芬心目中的英雄。

另一重點是「純音風格」,視弦樂的揉弦為必要時才使用的裝飾,而非演奏時的常態。不使用揉弦讓音樂更透明,突出結構與平衡感,追求乾淨、透明的音色,適用於十八至十九世紀音樂。諾林頓認為,持續的揉弦會掩蓋音樂的清晰度和時代風格的真實性,因此要求樂團以無揉弦的方式演奏,讓樂句的動態和表情更鮮明,增強音樂的「說話」感。他解釋:「揉弦如姚阿幸(Joseph Joachim)所述,是情感的替代品;十九世紀樂團多無揉弦,直到二十世紀初才普及。」

對諾林頓而言,歷史詮釋並非為了復古或「重現某個年代的聲音」,而是讓作品的結構與語氣更清晰、合乎創作時的邏輯。演奏的速度、力度、裝飾奏法、編制安排,皆應從作曲家的原始意圖與時代語境出發。他追求的不是懷舊,而是讓音樂在當下「重新活過來」。他以貝多芬《英雄》交響曲第二樂章〈送葬進行曲〉為例:「這不是四拍,而是很慢的二拍,因為人只有兩隻腳,狗的行進才四拍。」

諾林頓在二十一世紀初與斯圖嘉特廣播交響樂團(Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra)合作錄製貝多芬交響曲時,證明現代樂器也能模仿古樂風格,達到一樣的透明音色質感。諾林頓相信正確的演奏理念比樂器重要,一旦掌握恰當的編制、聲部平衡與音色控制等要素,現代樂器便能如古樂器般塑造出乾淨透明的紋理,讓音樂細節如白熾燈(White-Heat)般清晰(指音樂的強烈與直接,彷彿音樂被點燃,散發出熾熱的光芒,讓聽眾感受到每一個音符、樂句和結構的細膩之處)。

與倫敦古典演奏家古樂團的錄音相比,斯圖嘉特版的錄音更證實「純音風格」讓現代樂團的弧線拉得更寬廣,呼吸也更順暢。不須改變音樂詮釋,僅需在塑造樂句時把握適當的「姿態」(例如語法和動態對比),調整演奏的「能量」(演奏者注入的活力),在掌握這兩個大原則之後,即可自由發揮,得到該有的效果。諾林頓笑稱,這就像人在社會只要遵守該有的規矩後,便能自由行動、盡情發揮,而不致於犯錯。透過這些一貫的實踐原則,他放手大膽挑戰傳統,讓現代樂團重現古典作曲家的原始活力。

諾林頓一生無時不刻自問:「我們為什麼要這樣演奏?」他不是為了標新立異,而是堅信每首音樂都值得我們去思考其本質。他對聲音、節奏與語言的敏感,使他成為一位真正的音樂語法學家。他不強迫樂迷接受他的風格,但是他讓我們知道,在我們習慣的主流演奏風格之外,還有另一種角度可以聆聽貝多芬、舒曼、布魯克納。這種角度對很多人也許感到陌生,但也或許更貼近作曲家的初衷,更真實而富生命力。

British conductor Sir Roger Norrington passed away on July 18, 2025, at the age of 91. He was famous for promoting "Historically Informed Performance" (HIP), and he was especially known worldwide as a music history expert. He believed in an "evidence-based music" approach, which means strictly following the composer's original instructions, such as metronome marks, orchestra size, and using a "Pure-Tone Style" without vibrato. This helps bring the music back to its original time, avoiding the over-dramatic style of Romanticism. Norrington was not just a performer but also a world-famous music history scholar.

Norrington was born in Oxford in 1934. His father was a scholar, and his mother was an amateur pianist. They met while making amateur productions of operas by William Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan. So, Norrington's family education from a young age combined academic study with music performance. As a child, he learned violin and joined a choir. He studied English literature at the University of Cambridge and worked at Oxford University Press after graduation. During that time, he played violin, sang, and conducted as an amateur. It was only in the 1960s that he turned professional.

In the late 1950s, he entered the Royal College of Music in London and studied under conductor Sir Adrian Boult. In 1962, to perform works by the 17th-century German composer Heinrich Schütz, he founded the Schütz Choir. Recalling this turning point in his career, Norrington said: "As there was no Schütz tradition, Norrington had to invent a performing style, based on scholarship". This experience of looking back in time for answers laid the foundation for Norrington's later explorations in historical performance.

The Schütz Choir first worked with the London Baroque Players. In 1978, Norrington founded the London Classical Players (LCP), slowly moving from Baroque to Classical and Romantic periods. Norrington described this process as "from the seventeenth century onwards," where each new period felt like discovering a new world.

In 1969, Norrington became music director of Kent Opera, growing his influence in the British music world. He conducted over 40 operas there, with more than 400 performances. After founding the London Classical Players, his recording of Beethoven's complete symphonies from 1986 to 1988 became a milestone. This set used period instruments, followed metronome marks, and avoided vibrato, creating a pure and clear sound from the Classical period. The music was full of energy and freshness, with sharp, dramatic tones that changed how people thought about Beethoven.

His core idea of "evidence-based" performance means music playing must follow historical scores, documents, and the composer's notes, not the performer's own ideas. He stressed: "You don’t need an interpretation, you just need to get it right. The music should come crashing through without the conductor or the performers making it too much their own." This idea came from his early study of 17th-century music, later applied to 19th-century works. For example, following the composer's metronome marks—Beethoven was one of the first major composers to use modern metronome notation—he thought it was very important. Playing Beethoven's fast tempos makes the Eroica Symphony feel like an adventure, not grand and serious. He saw Beethoven as "late Haydn," focusing on his wit and humor, not like early Wagner's big drama. Some critics said his Eroica "doesn't sound very heroic." Norrington replied: "heroes don’t have to be bronze statues in the middle of a garden, surrounded by railings".

Another key point is the "Pure-Tone Style," where string vibrato is used only as a decoration when needed, not all the time. Without vibrato, the music becomes clearer, showing structure and balance better. It seeks a clean, clear sound for 18th- and 19th-century music. Norrington believed constant vibrato hides the music's clarity and true style of the time. So, he asked orchestras to play without vibrato, making phrases more lively and expressive, giving the music a "speaking" feel. He explained: "vibrato as Joseph Joachim described, is a substitute for real feeling; 19th-century orchestras mostly did not use vibrato, until the early 20th century".

For Norrington, historical performance is not about copying the past or "recreating the sound of a certain time," but making the work's structure and tone clearer and closer to the logic of when it was created. The tempo, dynamics, ornaments, and orchestra setup should come from the composer's original intent and the context of the time. He aimed not for nostalgia, but to make the music "come alive again" today. He used Beethoven's Eroica Symphony second movement, the Funeral March, as an example: "it’s not in four, it’s in a slow two. All marches are in two, because we have two feet. Maybe dogs march in four, but we don’t."

In the early 21st century, when Norrington worked with the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra to record Beethoven's symphonies, he showed that modern instruments can copy the old style and reach the same clear sound. Norrington believed the right playing ideas are more important than the instruments. Once you get the right size, balance, and sound control, modern instruments can create the same clean texture as old ones, like period instruments, making the music details shine like white-heat.

Compared to the recordings with the London Classical Players, the Stuttgart version shows that the "Pure-Tone Style" lets modern orchestras have wider arcs and smoother breathing. No need to change the music interpretation—just grasp the right "gesture" (like grammar and dynamic contrast) when shaping phrases, and adjust the "energy" (the vitality performers add). After getting these two main rules, you can play freely and get the right effect. Norrington joked that it's like people in society: follow the rules, then you can act freely and fully, without making mistakes. Through these steady practices, he boldly challenged tradition, letting modern orchestras bring back the original energy of Classical composers.

Norrington always asked himself: "Why do we play like this?" He did not aim to be different, but believed every piece of music deserves us to think about its true nature. His sensitivity to sound, rhythm, and language made him a true music grammar expert. He did not force fans to accept his style, but he let us know that besides the usual mainstream playing, there is another way to hear Beethoven, Schumann, Bruckner. This way may feel strange to many, but it might be closer to the composer's original idea, more real and full of life.

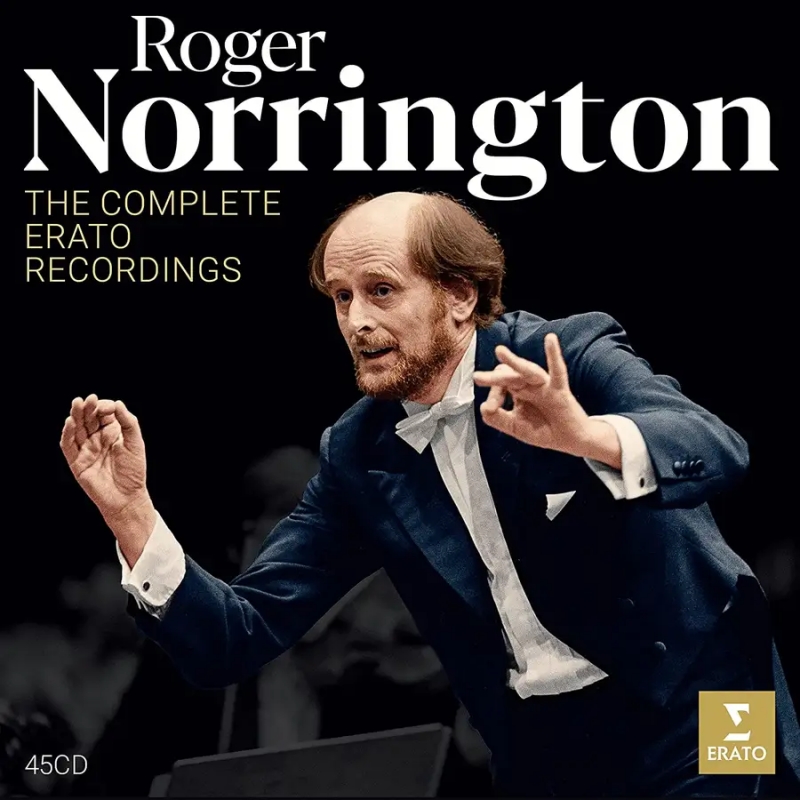

Roger Norrington: The Complete Erato Recordings

Recordings from 1986-2004

發表留言