一年的生命寓言:任奫燦的柴科夫斯基《季節》

柴科夫斯基《季節》(The Seasons)不能算是熱門的鋼琴獨奏曲。這套作品由雜誌《新樂家》(Нувеллист)在一八七五年委託創作,次年開始,每個月在雜誌上刊出一首,最後集結成十二個「月份」。曲調單純、篇幅短小,技術上並不艱深,因此常被視為「家庭沙龍小品」。然而正因為它的平易近人,真正的難題反而是:如何在這些簡單音符中,找出能觸動人心的重量。

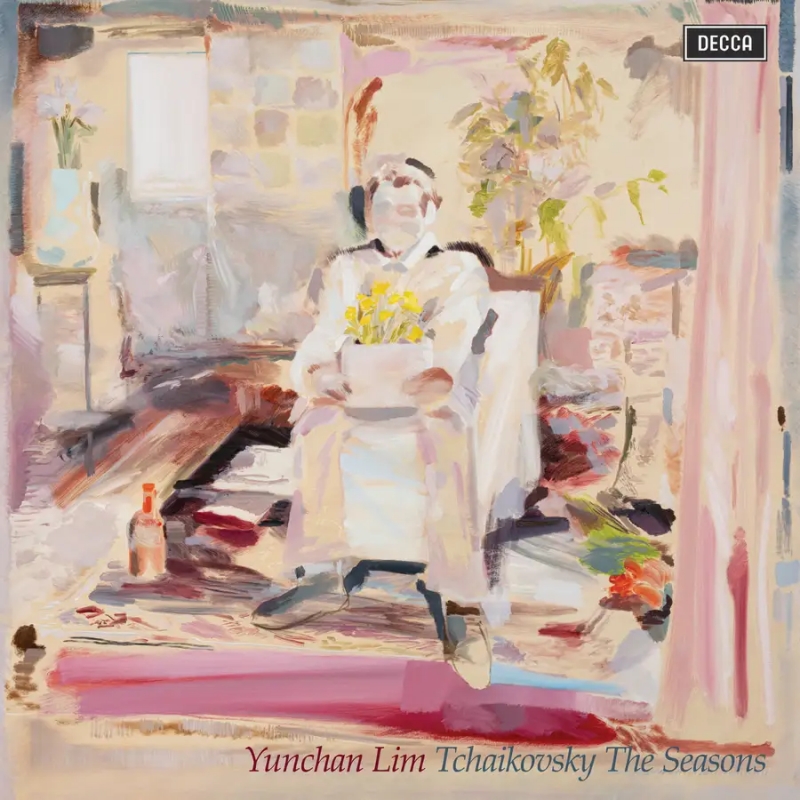

出乎意料的是,近兩年,有兩名鋼琴大賽冠軍都選擇《季節》為錄音題材:二○二一年蕭邦鋼琴大賽冠軍劉曉禹(Bruce Liu),二○二二年克萊本大賽冠軍任奫燦(Yunchan Lim),兩人相隔一年推出這套作品的專輯。對比下來,劉曉禹傾向於把它視為「音樂日記」,從簡單旋律裡尋找靜思的深度;任奫燦則轉化為「一個人生命的最後一年」寓言式敘事。這種大膽的想像,也引起樂評界的不同反應。

任奫燦的視角:一年的最後旅程

在專輯解說冊裡,任奫燦開宗明義指出:《季節》描繪的是一個人生命的最後一年。於是,十二首小曲不再只是月份的風景素描,而是被串聯成為一段生命走向終點的寓言。舉例來說,

〈一月:壁爐邊〉:火焰逐漸熄滅,男子在往事與現實間徘徊,時而流淚,時而接受,最後在鐘聲中關上「不再重來的一日」。

〈六月:船歌〉:整套曲目的核心。一名女子站在海邊想要自盡,凝望著星空,天使曾以燭光圍繞她,卻轉瞬離去,最後她沉入海中。

〈十月:秋之歌〉:任奫燦稱之為《季節》的「黑珍珠」。主角身在滿是落葉的街頭,懇求舊愛不要離去。旋律宛如愛迪‧琵雅芙(Édith Piaf)的嗓音,唱出逝去的愛與孤獨的死亡。

〈十二月:聖誕節〉:最後的告別。雪橇已遠去,主角帶著遺憾,最終決然道出「再見」。

在這樣的設計下,《季節》從「月份日曆」變成一段完整的人生敘事:從壁爐的餘燼,到臨終的孤獨與告別,最後步入無可逆轉的黑暗。

樂評界的質疑

出乎我意料之外的是,先前對任奫燦極盡讚譽的西方樂評人,這回對「生命最後一年」說法卻幾乎全部抱持保留態度,理由大致有幾點:

1. 與作品原初意圖不符

《季節》是柴科夫斯基受雜誌之託,每月提供一首供業餘鋼琴家彈奏的小曲,還附上相應詩句。它更接近沙龍娛樂或抒情小品,並非作曲家生死觀的寓言。任奫燦的「最後一年」的設定,被認為過於沉重,與原初的輕鬆性質相去甚遠。

2. 投射過多個人敘事

一些評論認為,任奫燦把自己的想像力過度加諸在作品之上,彷彿用故事去「覆蓋」音樂本身,而不是讓音樂自然而然流露。這樣的處理可能讓聽者感覺與柴科夫斯基的語言脫節。

3. 過度戲劇化

《季節》本身雖然有民俗色彩與抒情片段,但大體是溫婉、親切的音樂。任奫燦卻賦予它「自殺、死亡、最後告別」等極端戲劇性的情境,讓一些評論者覺得這是「異化」了柴科夫斯基。

簡而言之,反對者認為這種解讀「太沉重、太私人化」,並不是他們心目中應有的柴科夫斯基。

想像力的正面意義

然而回顧任奫燦過去的軌跡,他的詮釋方式一向帶著鮮明的「故事性」。在蕭邦《練習曲》專輯裡,他就為每首小品寫下具體畫面:宇宙大爆炸後面對無數星星、希臘人對特洛伊王子帕里斯綁架海倫的憤怒、莎士比亞《暴風雨》、里爾克的孤獨詩人⋯⋯這些想像未必符合歷史原貌,卻帶來了一種嶄新的閱讀角度。

柴科夫斯基的《季節》原本就是貼近日常,並不算「嚴肅」的大作品。或許正因如此,它才更適合被重新定義。任奫燦「最後一年」的概念,正好把這些單純的旋律提升到另一層次。即使與作曲家的初衷相去甚遠,卻為我們打開一扇新的門。對我來說,這完全不是我熟悉的柴科夫斯基,但是我認為這種「過度解讀」正是藝術的可能性所在。音樂史上有許多類似的例子,例如:貝多芬在升C小調鋼琴奏鳴曲第一樂章中,借用了莫札特《唐喬望尼》騎士長死亡場景的節奏,營造出徹爾尼所謂「鬼魂般的哀怨之聲」,然而後來的樂評家雷爾斯塔伯(Ludwig Rellstab)卻將此曲形容為「琉森湖上的月光」,此曲因而被後人稱為《月光》奏鳴曲;只有東亞地區稱為《革命》的蕭斯塔科維奇第五號交響曲⋯⋯這些想像從來不是作曲家親筆,而是後人對同一份樂譜的多重解讀。

因此,我樂見《季節》在任奫燦手中變成「一個人最後一年的生命寓言」。它或許不是我們熟悉的柴科夫斯基,但卻是我們這個時代年輕藝術家對作品的再創造。這樣的再創造,使我們能同時聽見兩種聲音:劉曉禹指下的《季節》,是靜謐的音樂日記;任奫燦指下的《季節》,是戲劇化的生命寓言。兩種版本互不抵觸,反而並存,提醒我們:同一份樂譜可以有截然不同的生命。

在我的觀念裡,重點不在於任奫燦心裡在想什麼,而是他彈出的音符能不能「說」出個道理說服我們。在這一點上,〈三月:雲雀之歌〉的彈性速度與層次、〈五月:白夜〉神秘的色彩、〈十月:秋之歌〉情感張力⋯⋯都是很值得欣賞的部分。

柴科夫斯基的《季節》原是貼近日常的月份素描,如今在劉曉禹與任奫燦手中,卻走向兩條截然不同的路:前者在簡單中尋找深度,後者則在小品裡建構寓言。任奫燦讓我們聽見的不只是十二個月份,而是一個靈魂最後的旅程。他的想像未必符合作曲家的歷史背景,卻提出了震撼人心的可能性:音樂也能成為生死寓言。

這種思路在專輯封面上得到具體化。韓國畫家崔浩然(Ho-yeon Choi)依任奫燦的構想繪製〈花瓣有多重?〉,以花瓣的輕與重象徵生命的矛盾,也呼應那場「最後一年」的寓言。於是,這張專輯同時面向不同層次的聽眾:專家能在其中探究結構與細節,初學者則可循著故事與圖像,直觀地觸及音樂的內在世界。這正是《季節》的啟示──同一份樂譜,能因不同演奏者而展現無數種生命,而任奫燦的版本,恰好為我們打開了另一扇窗。

Tchaikovsky’s "The Seasons" cannot be considered a staple of the solo piano repertoire. The work was commissioned by the magazine "Nouvellist" (Нувеллист) in 1875, with one piece published each month in 1876, later collected into twelve “months.” The melodies are simple, the scale modest, and technically the pieces are not difficult; thus, they have often been regarded as “salon miniatures for the home.” Yet precisely because of their accessibility, the true challenge lies elsewhere: how to find genuine weight within these simple notes.

Surprisingly, in the past two years, two winners of major international piano competitions have chosen "The Seasons" for their recordings: Bruce Liu, winner of the 2021 International Chopin Piano Competition, and Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn Competition. The two released their albums one year apart. In contrast, Liu treats the work as a kind of “musical diary,” finding depth in quiet simplicity, while Lim transforms it into an allegory of “the final year of a human life.” This bold imagination has, unsurprisingly, divided critical opinion.

Lim’s Perspective: The Final Journey of a Year

In his liner notes, Lim states unequivocally: "The Seasons" depicts “the final year in a person’s life”. In this way, the twelve short pieces cease to be mere sketches of each month; instead, they are woven into a narrative of life approaching its end. For example:

January: By the Fireside – the fire gradually dies out. A man wavers between past and present, sometimes weeping, sometimes resigning himself. At last, as the bell tolls, he closes “a day that will never come again.”

June: Barcarolle – the very heart of the cycle. A woman stands by the sea, ready to end her life. She gazes at the stars. Angels once encircled her with candlelight, but they vanish, leaving her alone; finally she sinks beneath the waves.

October: Autumn Song – which Lim calls the “Black Pearl” of "The Seasons". The protagonist, walking through streets strewn with fallen leaves, pleads with a former lover not to leave. The melody, Lim writes, sings with a voice like Édith Piaf, expressing lost love and a solitary death.

December: Christmas – the final farewell. The sleigh has already departed; the protagonist, left behind with regret, utters a last, decisive “goodbye.”

Thus, the original “calendar of months” is transformed into a full life story: from the fading embers of the hearth, through solitude and parting, to the irreversible darkness of death.

Criticism from the Music Press

What surprised me was that many Western critics—who had previously lavished praise on Lim—responded to this “final year of life” concept with notable reservations. Their objections fall into three main points:

1. Not aligned with the original intention

"The Seasons" was composed as short monthly pieces for amateurs, with accompanying epigraphs chosen by the editor. They are closer to salon entertainments or lyrical miniatures, not existential allegories. Lim’s “last year of life” setting was seen by some as too heavy, diverging sharply from the music’s lighter nature.

2. Excessive personal projection

Some reviewers argued that Lim imposed too much of his own narrative, “covering” the music with a story rather than letting it unfold naturally. This, they suggested, risks disconnecting from Tchaikovsky’s musical language.

3. Over-dramatization

While the pieces carry folk charm and lyricism, overall they remain gentle, intimate music. Lim, however, fills them with suicide, death, and final farewells. Critics saw this as an alienation of Tchaikovsky.

In short, the dissenting view is that Lim’s reading is “too heavy, too personal,” not the Tchaikovsky they recognize.

The Value of Imagination

Yet looking back at Lim’s earlier path, his interpretive style has always been vividly “story-driven.” In his Chopin "Études" album, for instance, he attached specific images to each piece: the Big Bang and countless stars, the rage of Greeks at Paris abducting Helen, Shakespeare’s "Tempest", Rilke’s solitary poet…. These visions are far from Chopin’s own intent, but they offer striking new angles of approach.

Tchaikovsky’s "Seasons" are rooted in everyday life and are not among his grandest works. Perhaps for this reason, they are particularly open to redefinition. Lim’s “last year” concept elevates these simple melodies to another plane. Even if distant from the composer’s original purpose, it opens a new door for us. For me, this is not the Tchaikovsky I thought I knew, but such “over-interpretation” is precisely where art finds possibility. Music history is full of examples: Beethoven’s Sonata in C sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 2, whose first movement recalls the death scene of the "Don Giovanni" Commendatore, was later renamed “Moonlight” by Ludwig Rellstab; Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 is known as the “Revolution” only in East Asia… none of these images came from the composer’s mind, but from later layers of interpretation.

In this sense, I welcome "The Seasons" being reshaped by Lim into “an allegory of the last year of life.” It may not be the Tchaikovsky we know, but it is a young artist’s recreation. This recreation allows us to hear two voices: Liu’s "Seasons" as a quiet diary, and Lim’s as a dramatic allegory. Far from canceling each other out, they coexist, reminding us that a single score can live many lives.

For me, the issue is not what Lim imagines privately, but whether his notes can “say” something that convinces us. In this respect, his flexible tempo and shading in "March: Song of the Lark", his nuanced "May: White Nights", and the expressive power of "October: Autumn Song" all merit admiration.

Conclusion: "The Seasons" Reborn

Tchaikovsky’s "The Seasons" began as modest monthly sketches. Now, in the hands of Liu and Lim, they diverge into two very different paths: the former seeking depth in simplicity, the latter building allegory from miniatures. Lim makes us hear not twelve months, but the final journey of a soul. His vision may not fit the composer’s historical background, but it offers a shockingly powerful possibility: that music itself can become a parable of life and death.

This idea is embodied visually on the album cover. Korean painter Ho-yeon Choi created "How Much Do the Petals Weigh?" at Lim’s request, using the lightness and heaviness of petals as symbols of life’s paradox. The artwork mirrors Lim’s allegory of the “final year.” Thus, the album addresses multiple audiences: experts can probe its structure and detail, while newcomers can follow the story and imagery to grasp the music’s inner world. This is the true revelation of "The Seasons": the same score can embody countless lives—and Lim’s version opens a new window for us.

TCHAIKOVSKY The Seasons

Yunchan Lim (piano)

31 July & 1 August 2024, The Menuhin Hall, Stoke d'Abernon, Surrey, England

發表留言