讓音樂自然生成:指揮家杜南伊的理念與風範

德國指揮杜南伊(Christoph von Dohnányi)於二○二五年九月六日在慕尼黑辭世,享壽九十五歲。他的離去,象徵歐洲戰後成長的一代大師正逐漸走入歷史。對許多愛樂者而言,他既代表德奧音樂家的理性分析傳統,也象徵嚴謹、樸實不浮誇的音樂精神。杜南伊出身具有匈牙利貴族血統,一九二九年在柏林出生,祖父是匈牙利作曲家、鋼琴家與指揮家艾爾紐・杜南伊(Ernst von Dohnányi),與布拉姆斯、李斯特有直接淵源。這樣的家族背景,讓年輕的杜南伊在音樂與思想上,都承繼了深厚的文化傳統與強烈的責任感。

一九四五年,律師父親與神學家舅舅因為參與反希特勒運動遭到處決,這段慘痛經歷深深烙印在當時年僅十五歲的杜南伊心中,也讓他下定決心避開政治,專注於音樂。杜南伊曾經說:「我本來想在戰後讀法律重建正義,但是音樂成了我的避難所。就像祖父那樣,用音符抵抗混亂。」他相信祖父在信中所寫的「音樂是重建世界的工具」,於是,杜南伊從慕尼黑大學(University of Munich)法律系轉入慕尼黑音樂與表演藝術大學(Hochschule für Musik und Theater München)學習作曲、鋼琴與指揮。一九五一年,他前往美國佛羅里達州立大學(Florida State University),跟隨曾經擔任布達佩斯音樂學院(Budapest Academy of Music)院長,二戰期間避居美國的祖父學習指揮與作曲。他回憶道:「祖父的第一堂課問我:『克里斯多夫,你會即興創作嗎?』我當時不會,但是他強調即興創作是音樂的核心。祖父討厭機械式練習,總是能即興演奏,甚至一次把整首奏鳴曲彈錯調卻渾然不覺。」因為即使偏離原調,祖父的演出依然具有說服力。這段經歷深深影響了杜南伊,使他日後更注重音樂的自然流動,而非僵硬的照本宣科。

杜南伊的職業生涯從歌劇院起步。一九五三年,他進入法蘭克福歌劇院(Oper Frankfurt)擔任蕭提(Georg Solti)的助理指揮。但是他戲稱,自己真正「出道」是一場臨時代打的芭蕾音樂會。由於早在鋼琴上熟悉這些曲目,他得以不看總譜就上台指揮。這次成功直接讓二十七歲的杜南伊獲得呂別克歌劇院(Lübeck Opera)總監的職位,成為當時德國最年輕的歌劇院音樂總監。

在法蘭克福歌劇院時期,杜南伊與比利時歌劇導演莫提耶爾(Gérard Mortier)攜手推動劇院革新。他們一方面維持傳統曲目的演出,一方面積極引入創新的音樂劇場與導演劇場(Regietheater),邀請格呂貝爾(Klaus Michael Grüber)、諾伊恩費爾斯(Hans Neuenfels)等導演合作,推出從布瑞頓到荀貝格的前衛作品。杜南伊親自指揮的《摩西與亞倫》、《伍采克》與《露露》更成為劇院代表性製作。這種兼顧傳統與現代的方針,不僅使法蘭克福成為德國最具前瞻性的歌劇院之一,也為日後莫提耶爾在歐洲各大劇院的改革奠下基礎。

杜南伊在二十世紀歌劇的推廣上也留下重要足跡。一九六五年,他在柏林德意志歌劇院指揮亨策(Hans Werner Henze)歌劇《年輕的君主》(Der Junge Lord)世界首演,亨策本人稱這是一次「排練與演出都極為出色」的經驗。翌年又在薩爾茲堡音樂節指揮亨策《酒神的信徒》(Die Bassariden)首演。這部作品大膽融合古典戲劇結構與當代音樂語言,獲得廣泛矚目。這兩部歌劇不僅奠定杜南伊在現代歌劇領域的聲望,也使他成為推動二十世紀新作進入國際舞台的重要指揮之一。

如果要為杜南伊的一生標記一段「黃金時期」,必定是他與克里夫蘭管弦樂團的十八年。一九八一年冬天,他首次在克里夫蘭登台指揮,出人意料地與音樂家們一拍即合。當時他的名氣遠不及前任總監塞爾(George Szell)與馬捷爾(Lorin Maazel),但是憑藉敏銳的耳力與低調而精準的指揮手勢,仍然迅速贏得樂團的信任。一九八四年正式成為樂團音樂總監,而且一待就是十八年。

在他的帶領下,克里夫蘭管弦樂團不僅延續塞爾時期的精確與紀律,更融入一種近乎室內樂般的精準、明晰默契。音樂家之間的傾聽、呼吸與對話,成為這支樂團獨一無二的標誌。杜南伊的音樂態度冷靜理性,卻能在克制的外表下激發樂曲蘊含的深刻內在張力,讓每一次演出都像初發表的新作般充滿生命力。一九九四年,該團甚至獲得《時代雜誌》「全美最佳樂團」的讚譽。

這十八年間,杜南伊錄製大量唱片,曲目既有厚重的德奧傳統,也有尖銳前衛的二十世紀作品。他帶領樂團進行超過十五次以上的世界巡演,足跡遍布歐洲與亞洲,甚至成為數十年來第一支駐薩爾茲堡音樂節的美國樂團,把「克里夫蘭」這個原本陌生的城市名稱,烙印在世界樂壇版圖上。杜南伊的視野不僅在演出與錄音,他也主導賽佛倫斯音樂廳(Severance Hall)大規模整修,讓長年沉睡的管風琴甦醒,在二○○○年以全新風貌重生。除此之外,他還創立青年管弦樂團與青年合唱團,把音樂的火種傳遞給下一代。這一切讓他的任期不僅是一段藝術合作,更是一場制度與文化的更新。

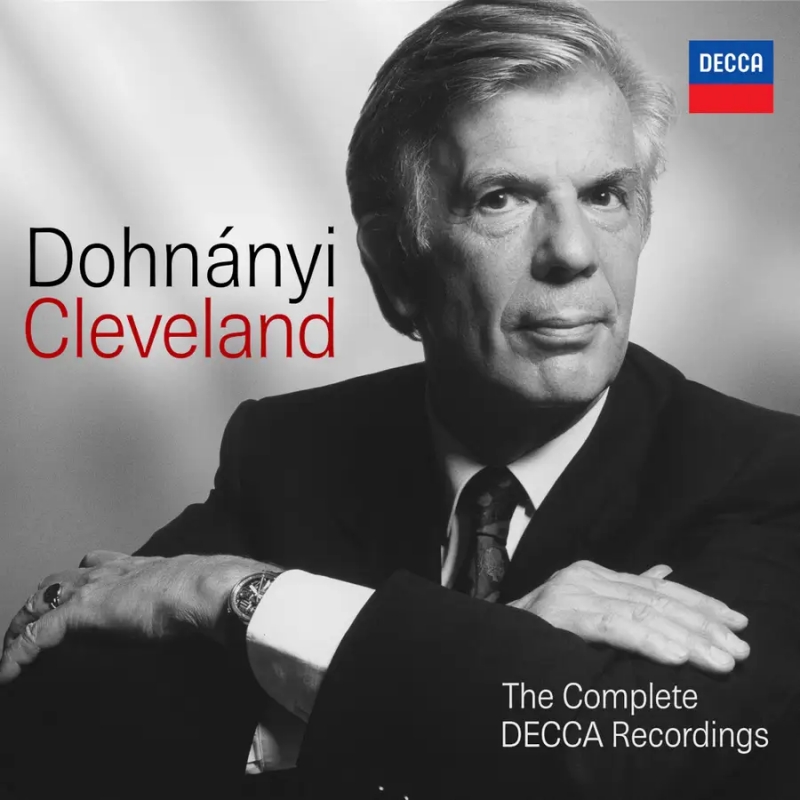

或許最令人惋惜的是未竟的華格納《尼貝龍的指環》錄音計畫。一九九○年代,他與笛卡原想留下完整錄音,最後卻只有《萊茵黃金》與《女武神》問世。然而,這些遺憾並未掩蓋成就。二○二四年,笛卡以《杜南伊與克里夫蘭管弦樂團笛卡錄音》(Christoph von Dohnányi – The Cleveland Years)套裝回顧這段歲月。四十張唱片、跨越十八年的錄音歷史,不僅是樂迷的珍藏,更是一個時代的縮影。

二○○二年卸任後,杜南伊並沒有急於退隱,而是轉向更自由的舞台。先後出任倫敦愛樂首席指揮、巴黎管弦樂團藝術顧問與漢堡北德廣播交響樂團首席指揮,並以客席身分活躍於波士頓、紐約、芝加哥等世界一流樂團。他也熱心培養後輩,長年與茱麗亞、寇帝斯及克里夫蘭音樂學院的學生樂團合作。杜南伊在二○一五年逐漸淡出舞台,但是仍以誠懇理性的聲音關注音樂與社會。對杜南伊而言,克里夫蘭是藝術生涯的高峰,晚年則是把這份經驗轉化為傳承與回望。

杜南伊曾經說,指揮的主要目標並不是凸顯自己,而是讓樂團彼此傾聽,讓音樂在對話中自然生成。對他而言,指揮並不只是舞台上的「樂趣」,而是一種能提升生命的偉大經驗;音樂的目的,也絕不僅止於娛樂,更在於讓人感受到精神與深度。他強調:「指揮的主要目標應該是讓自己顯得好似不重要,引導樂團團員演奏時彼此傾聽,自然的唱和,讓音樂自然生成。」又曾說:「我們需要讓人明白,挑戰也能是快樂的。當觀眾被音樂震撼時,他們會帶著興奮的心情回家,並熱切的思考,而不是無聊。」這樣的信念,正是他一生留給樂壇最珍貴的遺產,在他百年之後,也成為一種不朽的風範。

German conductor Christoph von Dohnányi passed away in Munich on September 6, 2025, at the age of 95. His departure symbolizes the gradual fading of a generation of postwar European masters. For many music lovers, he represented the rational analytic tradition of German-Austrian musicianship, while also embodying a spirit of sobriety, clarity, and freedom from exaggeration.

Dohnányi was born in Berlin in 1929 into a Hungarian aristocratic family. His grandfather was the Hungarian composer, pianist, and conductor Ernő (Ernst) von Dohnányi, who had direct ties to Brahms and Liszt. This lineage gave the young Christoph a deep cultural heritage and a strong sense of responsibility in both music and thought.

In 1945, his father, a lawyer Hans von Dohnányi, and his uncle, the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, were executed for their resistance against Hitler. This traumatic experience, imprinted on him at just fifteen, pushed him away from politics and toward music. Dohnányi once said:

“I originally wanted to study law after the war to rebuild justice, but music became my refuge. Like my grandfather, I resisted chaos with notes.”

He believed in what his grandfather had written in a letter: “Music is a tool for rebuilding the world.” Thus, Dohnányi transferred from law at the University of Munich to the Hochschule für Musik und Theater München to study composition, piano, and conducting. In 1951, he went to Florida State University to study with his grandfather, who had settled there after serving as director of the Budapest Academy of Music.

He recalled:

“My grandfather’s first lesson was to ask me: ‘Christoph, can you improvise?’ I couldn’t. But he insisted that improvisation is the core of music. He hated mechanical practice. Once, he even played an entire sonata in the wrong key without realizing it.”

This experience left a lasting mark, teaching him that music must flow naturally rather than cling rigidly to the score.

Dohnányi’s professional career began in opera. In 1953, he joined the Frankfurt Opera as assistant to Georg Solti. But his real “debut”, as he joked, was stepping in last-minute to conduct a ballet performance, relying only on his memory from the piano. The success earned him the position of Generalmusikdirektor at the Lübeck Opera at 27, making him the youngest GMD in Germany at the time.

At the Frankfurt Opera, he worked with Belgian director Gérard Mortier to push reforms. They maintained traditional repertoire while introducing bold new music theatre and Regietheater, collaborating with directors such as Klaus Michael Grüber and Hans Neuenfels. Productions of Moses und Aron, Wozzeck, and Lulu under Dohnányi’s baton became landmarks. This balance of tradition and innovation established Frankfurt as one of Germany’s most forward-looking houses and laid the groundwork for Mortier’s later reforms across Europe.

He also left a mark in 20th-century opera. In 1965, he conducted the world premiere of Hans Werner Henze’s Der Junge Lord at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, which Henze described as “brilliantly rehearsed and conducted.” The next year, at the Salzburg Festival, he led the premiere of Henze’s Die Bassariden, a daring fusion of classical drama and modern language that drew wide attention. These productions solidified his reputation as a champion of contemporary opera.

If one period could be called Dohnányi’s “golden age”, it was his 18 years with The Cleveland Orchestra. He first appeared there in 1981 and immediately connected with the musicians. Though less famous than his predecessors George Szell and Lorin Maazel, he quickly won trust with his sharp ear and precise, understated gestures. In 1984, he became music director and stayed until 2002.

Under his leadership, the orchestra preserved Szell’s discipline but added chamber-like clarity and intimacy. Musicians listened and breathed together, creating a unique identity. As Dohnányi himself explained in 2011:

“It’s an ensemble of musicians who come somehow from making chamber music. The real, very special (characteristic) about the Cleveland Orchestra is that people, musicians, are used to listen to each other very much. All orchestra should do it, many do it, but very few do it to the extent the Cleveland Orchestra is able to do it.”

Time magazine named Cleveland “the best band in the land” in 1994.

During these years, Dohnányi made more than 100 recordings, from the Austro-German canon to avant-garde works, and led over fifteen international tours. He also spearheaded the $37 million renovation of Severance Hall, restoring its long-silent organ. He founded the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra and Youth Chorus, ensuring music’s future. His tenure was not only artistic collaboration but also institutional renewal.

One project remained incomplete: Wagner’s Ring. Decca released Das Rheingold (1995) and Die Walküre (1997), but the cycle was abandoned as the recording industry collapsed. Yet in 2024, Decca issued the box set Christoph von Dohnányi – The Cleveland Years, 40 CDs spanning his tenure — a monument to that era.

After stepping down in 2002, he remained active, serving as principal conductor of London’s Philharmonia, artistic advisor to the Orchestre de Paris, and chief conductor of the NDR Symphony Orchestra in Hamburg. He guest-conducted in Boston, New York, Chicago, and beyond, while mentoring young musicians at Juilliard, Curtis, and the Cleveland Institute of Music.

In his later years, he valued transmission and reflection. To him, Cleveland was the peak of his artistic life, but afterward he turned that experience into legacy.

Dohnányi often stressed that the conductor’s role was not self-display but enabling dialogue among musicians:

“The main goal of a conductor should be that he is not important any more — that the orchestra listens to each other, that the orchestra has a certain spirit which you try to convey to them while you’re rehearsing.”

He also believed music was more than entertainment:

“We need to show that there is a possibility of being challenged in an enjoyable way because you wake up. You don’t go home with your wife bored, you have something to say: how horrible it was, how wonderful it was. It’s more exciting.”

For him, conducting was not just a pleasure but “a great experience that can elevate life.” His legacy lies in the conviction that music must be honest, clear, and alive — a heritage that endures beyond his century.

Christoph von Dohnányi – The Cleveland Years

發表留言