從《原神》到《幻想樂園》:陳致逸‧跨平台遊戲配樂‧DG當代音樂新思維

雖然百年古典大廠Deutsche Grammophon錄製的曲目常被批評過於保守,但是它們從來沒有忽略過當代音樂,目錄中有不少實驗性前衛作品,涵蓋戰後現代主義、序列音樂與聲響實驗,並且與多位當代作曲家建立長期合作關係。近二十年來,DG的策略重心出現更明顯的調整:擴大當代音樂的定義範圍,把活躍於電影與遊戲配樂領域,個人聲音已然成熟的創作者,納入自身的出版體系。像是把久石讓、約翰‧威廉斯(John Williams)這類早已深植流行文化的電影配樂巨擘作品,轉化為可在交響音樂會中演出,並且以唱片形式獨立流通,也發行希爾杜(Hildur Guðnadóttir)、約翰(Jóhann Jóhannsson)、高利霍夫(Osvaldo Golijov)這些橫跨影像、聲景與純音樂創作的作曲家作品。

同樣的邏輯,也出現在馬克斯‧李希特(Max Richter)、哈妮雅‧拉尼(Hania Rani)、葛瑞森(Peter Gregson)等作曲家身上。他們的作品旋律清楚、結構簡約,既能進入音樂會文化,也能適應串流時代的聆聽習慣。而環境音樂作曲家羅傑‧伊諾(Roger Eno)、極簡主義樂器合奏團白墨河(Balmorhea)⋯⋯的加入,顯示DG已經不再以諸如交響曲或協奏曲等傳統樂曲型式,當成衡量是否收錄到當代曲庫的固有標準。近年再加入具有跨文化背景的新世代作曲家,如:印尼作曲家尤妮克‧坦齊爾(Eunike Tanzil),這條「新當代」光譜的發展策略已經相當清晰。因此DG在中國成立分公司後簽下陳致逸並非破格之舉,而是新策略的順勢延伸。

對於大多數聽眾而言,第一次接觸「陳致逸」這個名字,應該是來自一款紅遍全球,由上海米哈遊推出的跨平台遊戲《原神》。這款遊戲推出後迅速累積龐大的下載量與營收規模,不僅在亞洲,也在歐美市場建立龐大的跨世代玩家社群。更重要的是,它讓「遊戲音樂」第一次如此大規模地進入日常聆聽環境,不再只是功能性的背景配樂聲。

在《原神》中,陳致逸不只進行個別創作,而是帶領整個配樂團隊,以交響語言統合遊戲所設定的「多重文化」音樂世界觀。其中「蒙德」、「璃月」這兩個遊戲中的國家配樂是陳致逸最具代表性的作品之一。他的作品以清楚的主題動機為核心,結合中國、日本、印度等傳統音樂語彙與西方管弦結構,使音樂在高度敘事性的同時,仍保有旋律與形式的高辨識度。這些特質讓「陳致逸」的名字隨遊戲風靡全球,不僅被大量非古典圈的聽眾所熟知,也成為他走向國際音樂舞台的契機。

在玩家社群與評論中,陳致逸的音樂經常被評論為遊戲「世界本身的一部分」,而不只是陪襯畫面的背景。即使玩家暫停操作、略過劇情文字,音樂仍能清楚勾勒出該地域的氣質、歷史感與情緒輪廓,彷彿這些虛擬的地域原本就該發出這樣的聲音。對玩家而言,音樂不僅標示「身在何處」,更是構築出這個幻想世界不可或缺的靈魂與骨架。然而,這張《幻想樂園》專輯,並不是《原神》遊戲的週邊延伸產品。

在深入《幻想樂園》(Fantasyland)之前,先簡單介紹陳致逸的成長背景。一九八四年出生於湖南長沙,成長於一個非專業音樂世家、卻充滿濃厚藝術氛圍的家庭:父親是數學教師,給予他理性的邏輯薰陶;母親受過聲樂訓練,後來為家庭放棄表演舞台。這種「理性結構與聲音感知並存」的環境,常被視為他日後同時重視理性結構與感性旋律的重要來源。陳致逸早年主修單簧管,先後就讀深圳藝術學校與上海音樂學院,從演奏訓練轉入作曲與音樂設計領域,接受完整的科班作曲、配器與音樂製作訓練。學生時期即參與影視與遊戲配樂實務,畢業後成立個人工作室,長期活躍於影像與遊戲音樂產業,逐步淬鍊出一套以交響結構為骨幹,並深度融合東亞傳統語彙與現代製作技術的個人音樂語言。

《幻想樂園》是陳致逸離開米哈遊旗下音樂工作室HOYO-MiX後,以作曲家個人名義推出的第一張完整專輯。與過往的遊戲配樂不同,這是一張刻意脫離角色、地區與劇情設定束縛的作品集,更接近一組以音樂自述的交響組曲,由齊格勒(Robert Ziegler)指揮倫敦愛樂管弦樂團錄製,陳致逸任鋼琴獨奏。除了傳統的交響樂編制,陳致逸還運用手風琴、印度班蘇里笛(bansuri)、西塔琴(sitar)、日本箏與尺八、中國笛子、二胡、古箏、琵琶等多元的民族樂器。

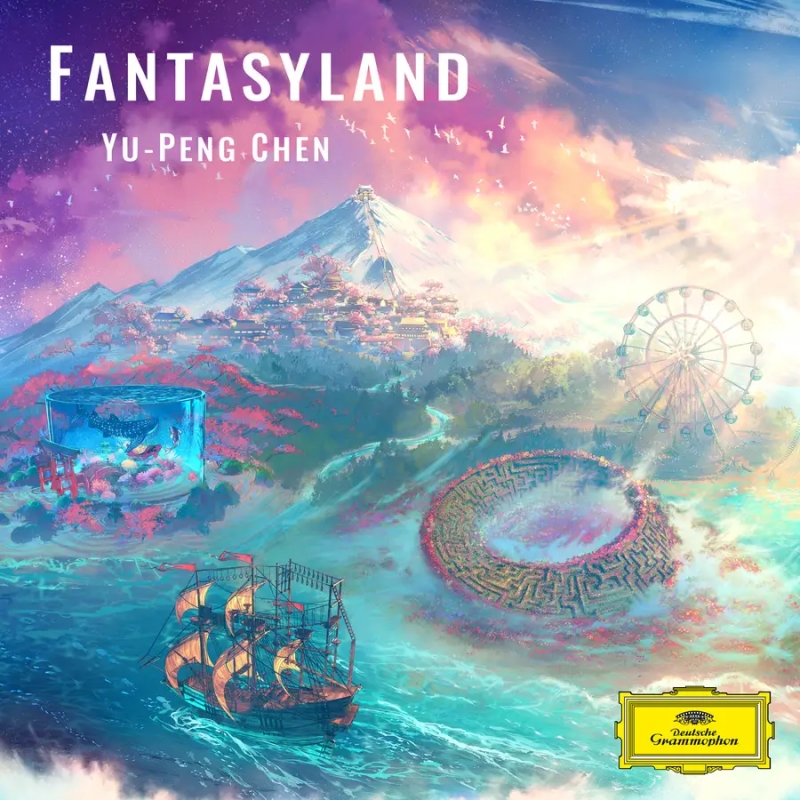

華裔畫家顏溫情繪製的唱片封面,更是精準的把整張專輯的聲音特質轉譯成視覺語言:層層展開的色彩、並存卻不衝突的空間元素,對應的是陳致逸音樂中多線並行的旋律、和聲與音色想像。畫面裡的山海、迷宮、航船與遊樂設施,不指向明確敘事,而是一種「可被自由遊走的幻想地形」。旨在讓聽者在多彩而開放的聲響中,自行開闢一條屬於自己的想像路徑。

音樂語言上,《幻想樂園》延續了陳致逸的招牌旋律感與清晰的管弦樂譜寫能力,但是敘事重心明顯內收,也就是音樂不再具體指向外部世界,而是圍繞著個人記憶、告別、想像與再出發等抽象主題展開;聽者的角度也從「辨認場景」轉為「感受結構與情緒」。如果陳致逸在遊戲配樂中的強項是「為遊戲世界觀服務的敘事能力」,那麼當《幻想樂園》不再依附於場景時,音樂是否仍然能吸引人?答案是肯定的。專輯中的音樂多半不急於堆疊高潮,而是透過層層推進的配器與動機,營造出一種行走流動的時間感。旋律保持高度的歌唱性,不受限於特定角色,而是讓聽者自行投射情緒與記憶。民族樂器特有的音色與調式也不作為表面的裝飾,而是被整合進管弦樂結構之中,成為完整音樂語言的一部分。兩支為《幻想樂園》拍攝的宣傳影片〈花與罪的無限迴廊〉與〈永夜之城的輪舞〉,影像也回到單純的音樂廳、交響樂團演奏現場,讓聽者不再透過多彩的敘事畫面,而是直接透過演奏效果走進陳致逸的音樂裡。

二○二五年推出《幻想樂園》「豪華版」實體唱片時,增加了四首曲目,都是陳致逸舊作的重新配器版。雖然無法收錄《原神》、《燕雲十六聲》這些當紅的跨平台遊戲配樂,但是改編自《逆水寒》〈瀾間輕步〉的〈夏日幻想〉,同時呈現管弦樂版與陳致逸彈奏的鋼琴獨奏版。鋼琴獨奏曲〈銀色入場券〉來自早期作品《旅人》;〈星幕下的旅棧〉則是改編自跨平台遊戲《無盡夢回》主題〈向無際彼岸〉。

《幻想樂園》並不是出自試圖證明「遊戲作曲家也能寫古典音樂」這種老式思維;相反地,它是直接展示作曲家的創作空間和內涵,探討當音樂不再服務特定媒介時,作曲家真正的內心獨白是什麼?《幻想樂園》成功的展現陳致逸獨立的音樂思維、創作手法,是陳致逸脫離大型IP後,為自己建立的一個有力的新起點;而他也用實力說明,為何他能有十足理由被DG納入當代作曲家版圖之中。

Although the repertoire recorded by the century-old classical label Deutsche Grammophon has often been criticised for being conservative, the company has in fact never neglected contemporary music. Its catalogue contains a substantial number of experimental and avant-garde works, ranging from post-war modernism and serialism to sound-based experimentation, and it has maintained long-term collaborations with many living composers.

Over the past two decades, however, DG’s strategic focus has become more clearly defined. The label has broadened its definition of contemporary music, bringing into its publishing system creators whose personal musical voices were shaped in film and game scoring, and whose styles have already reached artistic maturity. Figures such as Joe Hisaishi and John Williams, whose music is deeply embedded in popular culture, have seen their works transformed into repertoire suitable for symphonic concerts and issued as independent recordings. At the same time, DG has released music by composers such as Hildur Guðnadóttir, Jóhann Jóhannsson, and Osvaldo Golijov, whose work moves freely between film, soundscape, and autonomous concert music.

The same logic applies to composers such as Max Richter, Hania Rani, and Peter Gregson. Their music is melodically clear and structurally restrained, capable of inhabiting both concert culture and the listening habits of the streaming age. The inclusion of ambient composer Roger Eno and the minimalist instrumental ensemble Balmorhea further demonstrates that DG no longer treats traditional genres such as the symphony or concerto as fixed criteria for entry into its contemporary catalogue.

In recent years, the label has also welcomed younger composers with cross-cultural backgrounds, such as Indonesian composer Eunike Tanzil, making the contours of this “new contemporary” spectrum increasingly clear. Seen in this context, DG’s decision to sign Yu-Peng Chen after establishing its China branch is not a rupture, but a natural extension of this strategy.

For most listeners, their first encounter with the name Yu-Peng Chen likely came through “Genshin Impact", the globally successful cross-platform game released by Shanghai-based miHoYo. Following its launch, the game rapidly accumulated vast download figures and revenue, establishing a large, cross-generational player community not only in Asia but also across Europe and North America. More importantly, it allowed “game music” to enter everyday listening environments on an unprecedented scale, no longer confined to its former role as purely functional background sound.

In “Genshin Impact", Chen did not merely contribute individual pieces; he led an entire music team, using symphonic language to integrate the game’s multi-cultural musical world-building. Among the most representative examples of his work are the soundscapes for the in-game regions of Mondstadt and Liyue. Anchored by clearly defined thematic motifs, his music combines traditional musical vocabularies from China, Japan, and India with Western orchestral structures. As a result, the music achieves a high level of narrative clarity while retaining strong melodic presence and formal recognisability. These qualities brought Chen’s name to global attention alongside the game itself, reaching far beyond classical music circles and becoming a key stepping stone toward his international career.

Within player communities and critical discourse, Chen’s music is frequently described as an integral part of the game world itself rather than as mere accompaniment. Even when players pause gameplay or skip textual dialogue, the music alone can vividly define the atmosphere, historical depth, and emotional contours of each region, as though these virtual lands had always possessed their own inherent sound. For players, the music does more than indicate location; it forms the spiritual core and structural framework of the fantasy world.

Yet “Fantasyland" is not a peripheral product derived from “Genshin Impact".

Before turning to “Fantasyland", a brief overview of Chen’s background is helpful. Born in 1984 in Changsha, Hunan, he grew up in a family that was not professionally musical yet rich in artistic sensibility. His father was a mathematics teacher, providing a foundation of logical thinking, while his mother had received vocal training but later gave up her performing career for family life. This environment—where rational structure and sonic sensitivity coexisted—is often cited as a key influence on Chen’s later emphasis on both formal clarity and expressive melody.

Chen initially trained as a clarinetist and studied at the Shenzhen Arts School and later at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. He gradually transitioned from performance to composition and music design, receiving systematic training in composition, orchestration, and music production. During his student years, he was already involved in film and game scoring, and after graduation he founded his own studio. Over time, he developed a personal musical language built on symphonic structure, deeply integrated with East Asian traditions and contemporary production techniques.

“Fantasyland" is Chen’s first complete album released under his own name after leaving HOYO-MiX, the in-house music studio of miHoYo. Unlike his previous game scores, this album deliberately frees itself from the constraints of characters, regions, and narrative functions. It is closer to a symphonic suite of musical self-reflection. Recorded by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Robert Ziegler, with Chen himself as piano soloist, the album employs a traditional symphonic ensemble alongside a wide range of instruments: accordion; Indian bansuri and sitar; Japanese koto and shakuhachi; and Chinese instruments including dizi, erhu, guzheng, and pipa.

The album cover, painted by Chinese-American artist Yan Wenqing, translates the sonic character of the music into visual language with remarkable precision. Layers of colour and coexisting spatial elements mirror the parallel melodic lines, harmonic layers, and timbral imagination of Chen’s music. Mountains, seas, labyrinths, ships, and amusement structures appear not as fixed narratives, but as a “fantasy terrain” open to free exploration—inviting listeners to chart their own imaginative paths through a richly coloured sound world.

Musically, “Fantasyland" continues Chen’s signature melodic sensibility and clear orchestral writing, yet its narrative focus turns inward. The music no longer points toward an external world, but instead revolves around abstract themes such as memory, farewell, imagination, and renewal. The listener’s role shifts from recognising scenes to perceiving structure and emotional flow.

If Chen’s strength in game music lies in narrative service to world-building, the question arises: can his music still captivate when detached from concrete settings? The answer is affirmative. Rather than rushing toward climactic peaks, much of the album unfolds through gradual orchestration and motivic development, creating a sense of time in motion. The melodies remain highly lyrical, no longer bound to specific characters, allowing listeners to project their own emotions and memories. The timbres and modes of traditional instruments are not used as surface decoration, but are fully integrated into the orchestral fabric.

The two promotional videos produced for “Fantasyland"—"Infinite Cloister of Flowers and Sins" and “Circle Dance of Evernight Castle"—return visually to the concert hall, focusing on the orchestra in performance. By removing elaborate visual storytelling, they invite listeners to enter Chen’s music directly through sound alone.

When the “Fantasyland" Deluxe Edition was released in physical form in 2025, four additional tracks were included, all newly orchestrated versions of earlier works. While music from “Genshin Impact" or “Where Winds Meet" could not be included, “Summer Fantasy", adapted from “Justice Online"’s “Gentle Steps Between the Waves", appears in both orchestral and piano-solo versions performed by Chen himself. “Fantasyland’s Invitation" is a piano solo derived from his early work “Traveler", while “The Inn Beneath the Starry Sky" adapts “To Dream’s End" from the cross-platform game “The Neverending Dream".

“Fantasyland" is not an attempt to prove that “game composers can also write classical music”—a dated and unnecessary premise. Rather, it presents the composer’s creative space and inner substance, asking what remains when music is no longer tied to a specific medium. The album succeeds in articulating Chen’s independent musical thinking and compositional voice. As a personal point of departure after leaving a major intellectual-property framework, “Fantasyland" marks a strong new beginning—and convincingly demonstrates why Yu-Peng Chen belongs within Deutsche Grammophon’s contemporary composer landscape.

Fantasyland

Yu-Peng Chen (piano), London Philharmonic Orchestra, Robert Ziegler, Shanghai Philharmonic Orchestra

May 2024, Abbey Road Studio

April 2025, Largo Studio & Yu-Peng Music Studio

March 2025, Yu-Peng Music Studio

發表留言