從歷史註腳到重新賦予靈魂生命:隆多「路易‧庫普蘭計畫」,一場跨越三百年的音樂辯證

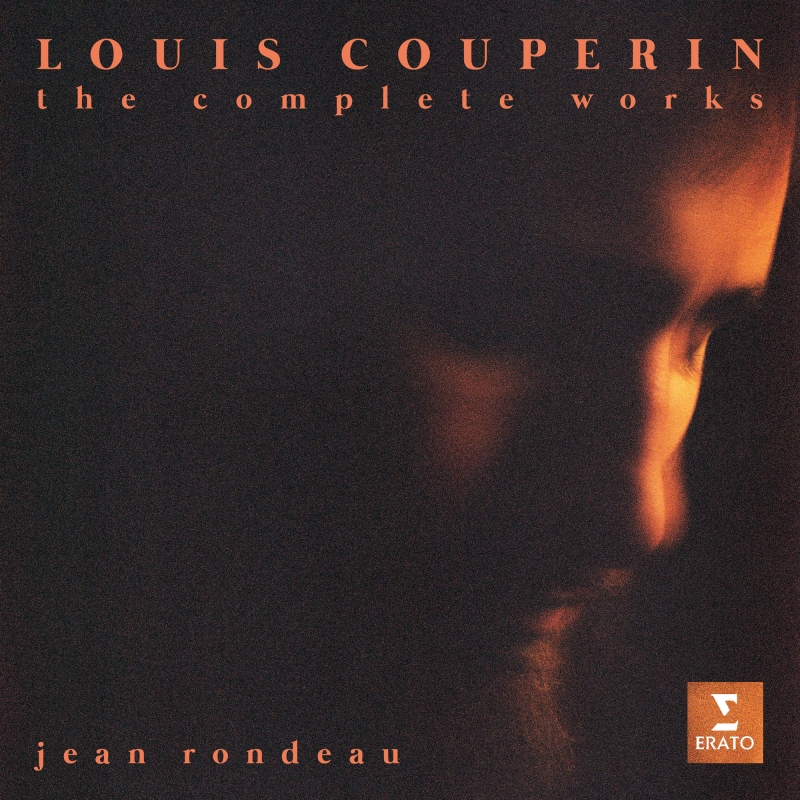

在當代古典唱片市場中,「作品全集」往往表示把某一位作曲家的作品盡量錄齊,成套出版。但是法國大鍵琴家隆多(Jean Rondeau)主導的這一套《路易‧庫普蘭作品全集》(Louis Couperin: The Complete Works)更像是一個經過長期準備、精心設計,一步步發展出來的探索或實驗計畫。

首先要釐清的是,此「庫普蘭」(Louis Couperin)並非大多數愛樂者熟悉的那個「庫普蘭」(François Couperin)。音樂史上,「庫普蘭」(Couperin)這個姓氏幾乎與弗朗索瓦‧庫普蘭劃上等號。這位被尊稱為「大庫普蘭」(le Grand Couperin)的音樂家,憑藉著確立法國鍵盤音樂的風格與語法,在歷史上留下不可撼動的名聲。然而,在這個輝煌的巴洛克音樂家族中,還有一位同樣關鍵卻常被忽略的人物,那就是弗朗索瓦的叔叔路易‧庫普蘭。他雖然是法國鍵盤音樂真正的奠基者,卻長期處於「大庫普蘭」的光環之下,成了名聲被掩蓋的先驅。

路易‧庫普蘭活躍於十七世紀中葉,約莫在一六五○年代踏入巴黎音樂圈,並任職於巴黎聖熱爾韋與聖普羅泰教堂(Église Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais de Paris)。他是法國鍵盤音樂由早期舞曲語言,推向更複雜表情與結構的重要人物之一。不過,路易‧庫普蘭在音樂史上的地位始終籠罩著一層迷霧,因為他沒有留下親筆手稿,當今看到的作品大多是由後人抄錄。這些標註「路易‧庫普蘭」名字的作品究竟是不是本人所寫,學界也沒有一致的答案。正因為如此,路易‧庫普蘭一方面被認為相當重要,另一方面卻又長期只在研究書籍或註腳之中露面,離聽眾始終隔著一段距離。

在這樣的背景下,隆多展開了他的「路易‧庫普蘭計畫」。這個計畫的起點並非出於學術補遺,而是一段源自童年時期的個人演奏經驗。當他彈奏路易‧庫普蘭的《無節奏前奏曲》(prélude non mesuré)時,這種只標示音高,卻不規定節奏的樂譜書寫方式,讓他意識到樂譜只是勾勒出音符的輪廓,真正的時間與呼吸,必須由演奏者選擇與回應。這就像一本只寫了台詞大意,演出時才由演員自行發揮的劇本。音樂最終的面貌,端看演奏家決定怎麼「說」。它介於即興與定稿之間,彷彿將作曲者的思考脈絡攤在紙上,要求演奏者一同思考,一同演繹,承擔著宛如共同創作般更大的詮釋責任。

這樣的音樂語言,也正好呼應隆多長期思考的問題:演奏者究竟有多少自由?在路易‧庫普蘭的時代,法國鍵盤音樂仍在發展成型中,舞曲組曲還沒有完全定型,而像「無節奏前奏曲」、「夏康」(chaconne)、「紀念曲」(tombeau)這些形式,也都還在摸索和演化,自然還沒有固定下來的演奏成規。路易‧庫普蘭的作品獨樹一格,常有不同於傳統法國舞曲的形式和規律,顯得更自由,允許停頓、拉長與轉折,讓和聲慢慢展開。這樣的寫法,顯示他受到義大利鍵盤樂器作品傳統的影響,也與德國作曲家弗羅伯格(Johann Jakob Froberger)的作品有相通之處。這些音樂不只是為了舞蹈而存在,更像是用來聆聽與思考的聲音藝術。因此,「路易‧庫普蘭計畫」從一開始就不只是單純的錄音計畫,而最初也僅規劃錄製大鍵琴作品。但是隨著愈來愈深入的研究與排練,隆多把觸角逐步擴展至管風琴與室內樂,並邀集多位音樂家共同參與;唱片曲序也是根據作品的樂器、形式分組安排,讓聽眾一步一步走進路易‧庫普蘭的音樂世界。

除了錄音與演出,「路易‧庫普蘭計畫」的重點之一,就是在法國科爾馬(Colmar)的「菩提樹下博物館」(Musée Unterlinden)拍攝影片《隆多演奏路易‧庫普蘭:組曲舞曲集》(Jean Rondeau joue Louis Couperin – Danses en suites)。不僅記錄演奏實況,也穿插簡短導聆,讓觀眾得以藉由視覺,「看見」演奏者如何在這些無節奏前奏曲與舞曲組曲中,實際做出節拍與音色的選擇,傳達出早期音樂中的即興特質。

在這套全集中,樂器選擇本身就是詮釋的重要一環。隆多刻意使用多台不同特性的大鍵琴,以及多座管風琴,讓同一位作曲家的作品,在音色、重量與空間感上呈現出差異。其中,勒克斯(Ruckers)系譜大鍵琴,聲音反應快、輪廓清楚,舞曲的節奏感特別分明;以這類大鍵琴演奏的無節奏前奏曲中,音符之間的停頓與推進,也顯得更鮮明清晰且富有呼吸感。至於管風琴作品則是依 照實際演奏場地的條件錄製,保留各個空間獨特的「聲響個性」,而不是透過後製來統一處理聲響效果。

在音樂詮釋層面,隆多自由大膽地運用「彈性速度」(rubato),讓和聲延展與樂句呼吸成為音樂推進的核心。這種處理方式與部分較為節制、強調舞曲形式的傳統詮釋形成對比,也因此在聽眾間引發不同的聆聽反應。然而正是這樣的詮釋態度,讓人更感受到隆多並不是把路易‧庫普蘭的音樂視作保存在博物館的歷史材料,而是發掘出作品的生命力,讓它可以持續被演奏與思考。

對聽者而言,這套全集提供了一條清晰的探索路徑:聽者不妨從無節奏前奏曲入手,感受音樂語言的自由。接著進入舞曲組曲,聆聽樂曲結構與細節發展的細微變化。最後進階則可以比較不同樂器與空間對同類型作品的影響,留意隆多如何推進細膩的和聲,以及塑造聲音的層次。《路易・庫普蘭作品全集》不是全部「路易・庫普蘭計畫」的終點,而是一個重要的階段里程碑。透過這個計畫,隆多讓路易・庫普蘭的作品從資料研究,轉為活生生的聆聽體驗,也為當代聽眾開啟一扇重新接近這位作曲家的大門,並為觀察法國音樂歷史風貌拓展寬廣的視野。

In today’s classical recording market, a “complete works” edition usually implies the attempt to record as comprehensively as possible the surviving output of a given composer, issued as a boxed set. Yet "Louis Couperin: The Complete Works", conceived and led by the French harpsichordist Jean Rondeau, resembles less a catalogue-driven undertaking than a carefully prepared, long-term process of exploration—almost an experimental project that has unfolded step by step.

At the outset, a clarification is necessary. This “Couperin” is not the figure most listeners immediately associate with the name: François Couperin. In music history, the surname Couperin has become almost synonymous with François Couperin, honoured as "le Grand Couperin". By defining the style and grammar of French keyboard music, he secured an unassailable place in the canon. Yet within this illustrious Baroque family stands another figure of equal historical importance but far less public recognition: François’s uncle, Louis Couperin. Although he was in many respects a true founder of French keyboard music, he has long remained in the shadow of his famous nephew, a pioneer whose reputation was eclipsed by later glory.

Louis Couperin was active in the middle of the seventeenth century. He entered the Parisian musical world around the 1650s and held the post of organist at the Church of Saint-Gervais–Saint-Protais in Paris. He played a crucial role in leading French keyboard music away from its early dance-based idiom towards greater expressive depth and structural complexity. Yet his historical position has always been clouded by uncertainty. No autograph manuscripts survive, and most of the works attributed to him are known only through later copies. Whether all the pieces bearing his name were in fact written by him remains a matter of scholarly debate. As a result, Louis Couperin has long been regarded as important, yet confined largely to academic literature and footnotes, separated from listeners by a persistent distance.

It was against this background that Rondeau began what he calls his “Louis Couperin project”. Its origins lie not in academic completeness but in a personal experience dating back to his childhood as a performer. When playing Louis Couperin’s "préludes non mesurés", notated with pitches but without fixed rhythm, he became aware that the score offers only an outline of sound. Time, breathing, and continuity must be shaped by the performer. It is rather like a theatrical script that provides only the essence of the dialogue, leaving the actor to determine delivery in performance. The final form of the music depends on how the performer chooses to “speak” it. Suspended between improvisation and composition, these works seem to expose the composer’s thought process on the page, inviting the performer to think and to shape alongside it, assuming a responsibility close to that of co-creation.

This musical language closely aligns with questions that have long preoccupied Rondeau: how much freedom does a performer possess? In Louis Couperin’s time, French keyboard music was still in formation. The dance suite had not yet crystallised into a fixed pattern, and forms such as the unmeasured prelude, the chaconne, and the "tombeau" were still evolving, without firmly established conventions of performance. Louis Couperin’s works often depart from the regularity of traditional French dance forms. They allow pauses, extensions, and turns that let harmony unfold slowly and deliberately. Such writing reveals the influence of Italian keyboard traditions and parallels with the music of Johann Jakob Froberger. These works are no longer conceived primarily for dancing, but rather as music to be listened to and reflected upon—sound as a medium of thought.

From the beginning, therefore, the Louis Couperin project was never merely a recording enterprise. It was initially planned as a harpsichord undertaking alone, but as research and rehearsal progressed, Rondeau gradually expanded its scope to include organ and chamber music, inviting other musicians to take part. The ordering of the recordings reflects this approach: works are grouped by instrument and form, guiding the listener step by step into Louis Couperin’s musical world.

Beyond recordings and concerts, one important element of the project is the filmed production "Jean Rondeau plays Louis Couperin: Dance Suites", shot at the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar. The film not only documents performance but also interweaves brief spoken reflections, allowing viewers to see how choices of tempo, articulation, and colour are made in real time—particularly in the unmeasured preludes and dance suites—and how improvisatory qualities central to early music are realised in practice.

Within the complete edition, the choice of instruments is itself a key interpretative factor. Rondeau deliberately employs several harpsichords of differing character, as well as multiple organs, so that the same composer’s music can be heard through contrasting sonorities, weights, and spatial responses. Harpsichords of the Ruckers tradition, with their quick response and sharply defined contours, bring particular clarity to dance rhythms. In unmeasured preludes played on such instruments, the pauses and forward motion between notes become especially audible, with a heightened sense of breath and articulation. The organ works, by contrast, are recorded according to the conditions of their specific venues, preserving each space’s distinctive acoustic identity rather than imposing a unified sound through post-production.

Interpretatively, Rondeau makes free and confident use of rubato, allowing harmonic expansion and phrasing to become the primary engines of musical motion. This approach contrasts with more restrained interpretations that emphasise strict dance character, and it has elicited differing responses among listeners. Yet it is precisely this stance that makes clear Rondeau’s fundamental attitude: Louis Couperin’s music is not a museum artefact to be preserved intact, but a living body of work to be explored, questioned, and continually reanimated.

For listeners, the complete edition offers a clear path of discovery. One may begin with the unmeasured preludes, experiencing the freedom of the musical language. From there, the dance suites reveal subtle developments of structure and detail. At a more advanced stage, listeners can compare how similar works respond to different instruments and acoustic spaces, observing how Rondeau shapes harmonic nuance and layers of sound. "Louis Couperin: The Complete Works" is not the conclusion of the Louis Couperin project, but a significant milestone within it. Through this undertaking, Rondeau transforms Louis Couperin’s music from a subject of archival study into a vivid listening experience, opening a renewed path towards this composer and widening our perspective on the landscape of French musical history.

LOUIS COUPERIN: THE COMPLETE WORKS

Jean Rondeau (harpsichord)

發表留言